Abstract

Background

Deprivation is associated with poorer survival after surgery for colorectal cancer, but determinants of this socioeconomic inequality are poorly understood.

Methods

A total of 4,296 patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer in 16 hospitals in the West of Scotland between 2001 and 2004 were identified from a prospectively maintained regional audit database. Postoperative mortality (<30 days) and 5-year relative survival by socioeconomic circumstances, measured by the area-based Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation 2006, were examined.

Results

There was no difference in age, gender, or tumor characteristics between socioeconomic groups. Compared with the most affluent group, patients from the most deprived group were more likely to present as an emergency (23.5 vs 19.5 %; p = .033), undergo palliative surgery (20.0 vs 14.5 %; p < .001), have higher levels of comorbidity (p = .03), have <12 lymph nodes examined (56.7 vs 53.1 %; p = .016) but were more likely to receive surgery under the care of a specialist surgeon (76.3 vs 72.0 %; p = .001). In multivariate analysis, deprivation was independently associated with increased postoperative mortality [adjusted odds ratio 2.26 (95 % CI, 1.45–3.53; p < .001)], and poorer 5-year relative survival [adjusted relative excess risk (RER) 1.25 (95 % CI, 1.03–1.51; p = .024)] but not after exclusion of postoperative deaths [adjusted RER 1.08 (95 %, CI .87–1.34; p = .472)].

Conclusions

The observed socioeconomic gradient in long-term survival after surgery for colorectal cancer was due to higher early postoperative mortality among more deprived groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Survival of patients with colorectal cancer is poorer among those from more socioeconomically deprived areas compared with more affluent areas.1–6 These socioeconomic inequalities have persisted and widened over time.2,4,6 It has been hypothesized that socioeconomic differences in survival may be explained by variations in disease stage at presentation, differences in treatment, or to the presence of comorbidities.7–11 However, the exact underlying causes for ongoing and widening socioeconomic inequalities in survival from colorectal cancer remain unclear. There is some evidence that patients from more deprived areas may experience delays in diagnosis and treatment and that diagnostic techniques and surgical approaches differ.12–14 The excess mortality among more deprived patients was largely found in the first year, and particularly the first month, of follow-up, raising further questions about whether late presentation was the major determinant of the socioeconomic differential.15

Despite high-quality collection of a range of variables, studies based on national cancer registry data do not contain comprehensive information on clinical management or tumor-related factors that may explain the observed socioeconomic survival gradients. Surgery performed under the care of a specialist colorectal surgeon, for example, is associated with improved cancer-specific survival.16 However, surgical specialization is not recorded within cancer registry data. While clinical studies of patients from Scotland during the 1990s have confirmed both overall and cancer-specific survival following curative surgery for colorectal cancer was lower in deprived patients, they did not find that stage of disease at presentation or operation type explained this survival difference.17 However, more recent clinical series have shown that deprivation remains associated with poorer survival after surgery for both colon and rectal cancers.18,19

One specific difficulty in comparing socioeconomic analyses of colorectal cancer survival has been that previous reports have used different methodologies to classify deprivation that mainly focus on household income. Although they often occur together, deprivation does not directly equate with poverty. Deprivation is therefore a difficult concept to define but can be thought of as one end of a socioeconomic spectrum characterized by both material and social disadvantage relative to the population under study. In Scotland socioeconomic circumstances are measured using the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD). The SIMD score is an area-based index that uses information on a range of social and material variables to allow comparison of areas of high deprivation to more affluent areas.20

Therefore, the aim of this study is to examine the influence of socioeconomic circumstances short- and longer-term survival in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer using a robust measure of deprivation in a large clinical series for which detailed data on case-mix were available.

Methods

Clinical audit data of patients undergoing surgery for a primary colorectal cancer in 16 hospital sites from January 1, 2001 to December 31, 2004 were extracted from the prospectively maintained database of the West of Scotland Colorectal Cancer Managed Clinical Network. Individual patient records were then linked to the Scottish Cancer Registry (SMR6). Details included age, gender, deprivation category, mode of presentation, site of tumor, Duke’s stage, intent of surgery, and specialty of surgeon (colorectal specialist or nonspecialist).

Tumors were classified according to their anatomical site as per the International Classification of Disease version 10 (ICD-10). Lesions from the cecum to the sigmoid colon were classified as colon cancers (C18). Carcinomas of the rectosigmoid junction and rectum were classified as rectal cancers (C19–C20). Tumors of the appendix (C18.1) and anus (C21) were excluded. The extent of tumor spread was assessed by conventional hybrid Duke’s staging based on histological examination of the resected specimen and radiology reports. Patients were deemed to have had a curative resection if the surgeon considered that there was no macroscopic residual tumor once the resection had been completed and was verified histologically as a complete resection (R0). Surgery was deemed palliative if there was either incomplete (R1 or R2) or unresectable local or distant disease at time of surgery, or as identified preoperatively from staging investigation. Mode of presentation was defined as emergency if presentation was via an unplanned hospital admission with significant rectal bleeding, intestinal obstruction, or perforation. Individual surgeons were identified as colorectal specialists or nonspecialists by panel members of the corresponding colorectal cancer multidisciplinary team (MDT) of the hospitals under study in similar way to earlier studies.16

Deprivation was measured using the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) 2006 score.20 It provides an area-based measure of socioeconomic circumstance, based on the postcode of residence. There are 6,505 geographical small areas or data zones across Scotland, each containing approximately 750 people. The SIMD score provides a relative ranking of these 6,505 areas from the most to the least deprived, based on detailed information on 7 key subject areas: (1) income and benefits, (2) employment in working age population, (3) health and healthcare utilization, (4) educational attainment, skills, and training, (5) access to services and transport, (6) recorded crime rates, and (7) housing quality and overcrowding. The score generated for each key subject area (weighted toward income, employment, and education) is ultimately combined to create an overall SIMD score for each data zone. Overall, SIMD (2006 version) scores are presented as quintiles, with 1 representing the least deprived and 5 representing the most deprived, each representing 20 % of the Scottish population. Therefore, those in the most deprived fifth are more likely to have higher levels of poverty, unemployment, poorer quality housing, and lower educational attainment compared with those from the least deprived fifth.

All patient records were linked to their Scottish Morbidity Record 1 (SMR1) records. These provide a comprehensive record of all day case and inpatient admissions to general hospitals in the country. SMR1 records were used to calculate the number of hospital inpatient bed-days in the period of 5 years up to 6 months preceding diagnosis of colorectal cancer as a crude indicator of general pre-existing comorbidity; an adaptation of a previously described methodology.11

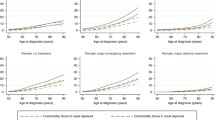

Patient records were linked to General Registry Office for Scotland (GROS) death records. Minimum follow-up of survivors was 5 years. Postoperative mortality was defined as any death occurring within 30 days of surgery. Relative survival is expressed as the ratio of the overall survival and the survival that would be expected when exposed only to the background mortality of a specific population. Annual age, gender, and SIMD-specific Scottish life tables produced by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine were used to estimate background population mortality.

Statistical Methods

Comparisons of the association between baseline clinicopathological characteristics, treatment variables, and socioeconomic group were made using the χ 2 test for trend where appropriate. Survival time was calculated from date of surgery to the date of death or censor with a minimum of 5 years follow-up (date of censor December 31, 2010). Patients were excluded from the survival analysis if no follow-up time was calculable (i.e., patient died on day of surgery). Factors associated with postoperative mortality were identified using univariate and multivariate logistic regression models. Relative survival was used to estimate 5-year survival. The Hakulinen-Tenkanen approach to model excess mortality was used for the multivariate relative survival analysis. Relative excess risk (RER) ratios are presented with 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI), and p < .050 was considered statistically significant. Analysis was performed using STATA software package version 11(IC).21

Results

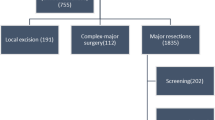

A total of 4,296 patients (54.0 % male) who underwent surgical treatment for primary colorectal cancer, from January 1, 2001 to December 31, 2004, were included. The mean age was 69.8 years (range, 21.2–97.8 years). The mean follow-up period was 4.5 years (range, 0–10.1 years).

Univariate associations between baseline clinicopathological characteristics and socioeconomic groups are shown in Table 1. Patients from the most deprived areas were more likely to have been hospitalized in the previous 5 years (most deprived vs most affluent, 58.2 vs 54.8 %; p = .03), to present as an emergency (23.5 vs 19.5 %; p = .033), to have <12 lymph nodes examined (56.7 vs 53.1 %; p = .016), to undergo a palliative rather than curative resection (20.0 vs 14.5 %; p < .001), and to be operated on by a specialist surgeon (76.3 vs 72.0 %; p = .001). Socioeconomic circumstances were not associated with age, gender, Duke’s stage, site of tumor, tumor differentiation, or extramural vascular invasion.

Overall, 308 patients (7.2 %) died within 30 days of surgery. Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with postoperative mortality are shown in Table 2. Deprivation was an independent predictor of postoperative mortality. Compared with the most affluent, the most deprived had a more than a 2-fold increased risk of dying within the first 30 days of surgery [adjusted odds ratio 2.26 (95 % CI, 1.45–3.53; p < .001)]. Advancing age, 8 or more inpatient bed-days in the previous 5 years, emergency presentation, poor tumor differentiation, low lymph node yield (<12 lymph nodes), and noncurative surgery were also independently associated with increased postoperative mortality.

At 5 years following surgery, 2,166 patients (50.4 %) had died; 8 patients (.2 %) died on the day of surgery and were excluded from the relative survival analysis. The 5-year relative survival rate was 61.7 % (95 % CI, 59.8–63.6). Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with 5-year relative survival are shown in Table 3. Survival rates were highest among the most affluent groups. Deprivation was independently associated with poorer survival, with the most deprived group having a 25.0 % increased risk of dying from colorectal cancer compared with the most affluent group [adjusted RER 1.25 (95 % CI, 1.03–1.51; p = .024)]. Advancing age, 8 or more inpatient bed-days in the previous 5 years, emergency presentation, more advanced Duke’s stage, poorly differentiated tumors, extramural vascular invasion, <12 lymph nodes examined, and noncurative surgery were also significantly associated with poorer 5-year relative survival in the adjusted model.

The univariate (unadjusted) and multiply-adjusted 5-year RER by socioeconomic group are shown in Table 4. To investigate the influence that early mortality had on the observed socioeconomic survival differential at 5 years, the RER conditional on surviving the postoperative period was calculated. After exclusion of postoperative deaths, socioeconomic circumstances were no longer significantly associated with poorer relative survival. Compared with the most affluent patients, survival in those from the most deprived areas were not significantly different [adjusted RER 1.08 (95 % CI, .87–1.34; p = .472)].

Discussion

In this study, deprivation was independently associated with both poorer short- and longer-term survival following surgery for colorectal cancer. Higher postoperative mortality among patients from more deprived areas appears to be the main determinant of socioeconomic variations in longer-term survival; among patients who survived the postoperative period, we found no significant difference in survival between socioeconomic groups.

These present findings are consistent with recent evidence from the United Kingdom that identified the greatest socioeconomic differentials in survival within the first month after diagnosis and a smaller effect over the rest of the first year in cancer registry data.15 Similarly, a recent study of postoperative deaths after colorectal cancer surgery in England showed that postoperative mortality was higher among those from the most deprived areas after adjustment for operative urgency, stage of disease, and comorbidity.22 In contrast, other series have failed to find an association between deprivation and postoperative mortality when American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) score was included in the adjusted models as a marker of preoperative comorbidity, suggesting that socioeconomically patterned differences in perioperative physiology may have a role.1,18 However, deprivation was independently associated with postoperative death after adjustment for other factors including mode of presentation to surgery, tumor stage, and a proxy measure of comorbidity in the present study.

The 5-year relative survival rate following surgery was 61.7 %. Relative survival at 5 years was significantly poorer among the most deprived compared with the most affluent. Previous studies examining longer-term outcome after surgery for colorectal cancer have shown that deprivation was associated with poorer overall and cancer-specific survival.1,3,10,17 Relative survival estimates for this population are recognized as superior to overall and cause-specific survival as variations in background mortality rates between socioeconomic groups can be adjusted for to allow the true effect of the disease under study to be more accurately assessed.23,24 Only 1 other clinical series examining the influence of socioeconomic circumstances on outcome after surgery for colorectal cancer using similar relative survival methodologies has been previously published.18 As in the present study, Bharathan et al. reported that longer-term relative survival after surgery for colorectal cancer was poorest among the most deprived. The present study further examines the influence of early socioeconomic survival differentials on longer-term survival by including a conditional survival analysis. This demonstrates that the main determinant of the observed longer-term socioeconomic relative survival differential was the excess postoperative morality among the more deprived groups in this series.

The principal strength of this study is that it includes a range of clinical variables not routinely included in existing cancer registry data. Studies reporting socioeconomic inequalities using cancer registry data alone are unable to adjust for such variables, potentially leading to an overemphasis of the true impact of deprivation. The prospectively collected data within the West of Scotland Colorectal Cancer Managed Clinical Network audit contains detailed clinicopathological and treatment information not routinely collected by the Scottish Cancer Registry. Therefore, by linking both cancer registry and clinical audit data the design of this study enables a detailed exploration of the extent to which socioeconomic inequalities influence survival.

The West of Scotland has the scientific advantage of being able to generate large populations of both affluent and deprived patients with which to compare and contrast health outcomes. This study therefore comprises a large sample from a socioeconomically diverse and representative group of colorectal cancer patients with a wide range of socioeconomic inequality. This allows for trends in outcomes due to deprivation to be more easily recognized. This series also uniquely includes details of lymph node yield and specialization of surgeon that have not previously been included as covariates in other similar published series.

Limitations of this study concern incompleteness of data fields (e.g., pathological data). Details of Duke’s stage of disease were missing in 4.1 % of this cohort compared with 1.8 and 10 % in other series.18,22 The lack of inclusion of other desirable variables (e.g., ASA grade, body mass index, smoking history) is also a limitation of this study. The use of previous inpatient bed days may be a less-sensitive marker of comorbidity in this population compared with other measures (e.g., Charlson comorbidity index or ASA grade), leading to inadequate adjustment. Previous studies using this method have found it to be a useful tool where other comorbidity data are missing.11 Continued clinical research to explore the potential confounding effects of patient-related risk factors and comorbidities is merited.

In conclusion, patients from the most deprived areas had poorer short- and longer-term survival following surgery for colorectal cancer compared with those from the most affluent areas in this study. The observed socioeconomic gradient in long-term survival was due to higher early postoperative mortality among more deprived groups.

References

Smith JJ, Tilney HS, Heriot AG, Darzi AW, Forbes H, Thompson MR, et al. Social deprivation and outcomes in colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2006;93:1123–1131. doi:10.1002/bjs.5357.

Shack LG, Rachet B, Brewster DH, Coleman MP. Socioeconomic inequalities in cancer survival in Scotland 1986–2000. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:999–1004. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6603980.

Byres TE, Wolf HJ, Bauer KR, Bolick-Aldrich S, Chen VW, Finch JL, et al. The impact of socioeconomic status on survival after cancer in the United States. Cancer. 2008;3:582–91. doi:10.1002/cncr.23567.

Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, Singh GK, Cardinez C, Ghafoor A, et al. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:78–93. doi:10.3322/canjclin.54.2.78.

Egeberg R, Halkjoer J, Rottmann N, Hansen L, Holten I. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from cancers of the colon and rectum in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994–2003. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1978–1988. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2008.06.020.

Rachet B, Ellis L, Maringe C, Chu T, Nur U, Quaresma M, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in cancer survival in England after the NHS cancer plan. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:446–453. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6605752.

Singh GK, Miller BA, Hankey BF, Edwards BK. Area socioeconomic variations in US cancer incidence, mortality, stage, treatment and survival, 1975–1999. NCI Cancer Surveillance Monograph Series, Number 4. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2003. Publication No. 03-5417.

Guyot F, Faivre J, Manfredi S, Meny B, Bonithon-Kopp C, Bouvier AM. Time trends in the treatment and survival of recurrences from colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:756–61. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdi151.

Yu XQ, O’Connell DL, Gibberd RW, Armstrong BK. A population-based study from New South Wales, Australia 1996-2001: area variation in survival from colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2715–21. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2005.02.018.

Wrigley H, Roderick P, George S, Smith J, Mullee M, Goddard J. Inequalities in survival from colorectal cancer: a comparison of the impact of deprivation, treatment, and host factors on observed and cause specific survival. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:301–9. doi:10.1136/jech.57.4.301.

Brewster DH, Clark DI, Stockton DL, Munro AJ, Steele RJ. Characteristics of patients dying within 30 days of diagnosis of breast or colorectal cancer in Scotland, 2003–2007. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:60–7. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6606036.

MacLeod U, Mitchell ED, Burgess C, MacDonald S, Ramirez AJ. Risk factors for delayed presentation and referral of symptomatic cancer: evidence for common cancers. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:S92–S101. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6605398.

Legeune C, Sassi F, Ellis L, Godward S, Mak V, Day M, et al. Socio-economic disparities in access to treatment and their impact on colorectal cancer survival. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:710–7. doi:10.1093/ije/dyq048.

Cavalli-Björkman N, Lambe M, Eaker S, Sandin F, Glimelius B. Differences according to educational level in the management and survival of colorectal cancer in Sweden. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1398–406. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2010.12.013.

Moller H, Sandin F, Robinson D, Bray F, Klint S, Linklater KM, et al. Colorectal cancer survival in socioeconomic groups in England: variation is mainly in the short term after diagnosis. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:46–53. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2011.05.018.

McArdle CS, Hole DJ. Influence of volume and specialization on survival following surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2004;91:610–7. doi:10.1002/bjs.4456.

Hole DJ, McArdle CS. Impact of socioeconomic deprivation on outcome after surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2002;89:586–90. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02073.x.

Bharathan B, Welfare M, Borowski DW, Mills SJ, Steen IN, Kelly SB, et al. Impact of deprivation on short- and long-term outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery. Br J Surg. 2011;98:854–65. doi:10.1002/bjs.7427.

Harris AR, Bowley DM, Stannard A, Kurrimboccus S, Geh JI, Karandikar S. Socioeconomic deprivation adversely affects survival of patients with rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2009;96:763–8. doi:10.1002/bjs.6621.

Scottish Government. Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation. 2010. Available at: http://www.scotland.gov.uk/topics/statistics/SIMD. Accessed 21 Sept 2012.

Statacorp, College Station, TX: Statacorp LP. Stata Statistical Software: Release 11. 2009; 11(IC).

Morris E, Taylor EF, Thomas JD, Quirke P, Finan PJ, Coleman MP, et al. Thirty-day postoperative mortality after colorectal cancer surgery in England. Gut. 2011;60:806–13. doi:10.1136/gut.2010.232181.

Berrino F, Estève J, Coleman MP. Basic issue in estimating and comparing the survival of cancer patients. In Survival of Cancer Patients in Europe. The EUROCARE Study. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer 1995; No 132: 1–14.

Dickman PW, Sloggett A, Michael Hills M, Hakulinen T. Regression models for relative survival. Stat Med. 2004;23:51–64. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdi151.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank all the surgeons who participated, the West of Scotland Colorectal Cancer Managed Clinical Network advisory board who gave permission for MCN audit data to be used in this study, and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine for providing the Scotland-specific life tables used in the relative survival analyses. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oliphant, R., Nicholson, G.A., Horgan, P.G. et al. Deprivation and Colorectal Cancer Surgery: Longer-Term Survival Inequalities are Due to Differential Postoperative Mortality Between Socioeconomic Groups. Ann Surg Oncol 20, 2132–2139 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-013-2959-9

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-013-2959-9