Abstract

The large number of active combination chemotherapy regimens for most cancers has led to the need for better information to guide the ‘standard’ treatment for each patient. In an attempt to individualise therapy, pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics (a polygenic approach to pharmacogenetic studies) encompass the search for answers to the hereditary basis for interindividual differences in drug response. This review will focus on the results of studies assessing the effects of polymorphisms in drug-metabolising enzymes and drug targets on the toxicity and response to commonly used chemotherapy drugs. In addition, the need for polygenic pharmacogenomic strategies to identify patients at risk for adverse drug reactions will be highlighted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

In the UK it has been estimated that approximately 7% of patients are affected by adverse drug reactions (ADRs). Indeed, one out of 10 of all NHS bed days are used by patients with ADRs. These ADRs result in the need for the equivalent of 15–20 400-bed hospitals and cost about £380 million a year. ADRs due to cancer chemotherapy are estimated to increase the overall hospital costs by 1.9% and drug costs by 15% (Wiffen et al, 2002). Clearly, the current regimen of ‘one dose fits all’ for chemotherapy treatment is not ideal for patients and is not cost effective for the health service. In an attempt to individualise therapy, pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics (a polygenic approach to pharmacogenetic studies) encompass the search for answers to the hereditary basis for interindividual differences in drug response (Evans and McLeod, 2003).

In addition to environmental influences, variation in the genetic constitution between individuals will have a major impact on drug activity. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) account for over 90% of genetic variation in the human genome. The remainder of the variation is caused by insertions and deletions (indels), tandem repeats and microsatellites. With the completion of the human genome project, there has been an explosion in the discovery, characterisation and validation of genetic variation. Over 1.42 million SNPs were initially identified through the human genome project (Sachidanandam et al, 2001), and a goldmine of SNP information is now readily accessible via publicly available databases (Marsh et al, 2002). In addition, affordable, high throughput genotyping technologies are now available, including Pyrosequencing, FP-TDI, MALDI-TOF and SNP chips, making pretreatment genotyping a real possibility. A comprehensive review of the technology available to pharmacogenetics research is beyond the scope of this minireview; however, there are many excellent reviews describing these applications (Kwok, 2001; Shi, 2001; Syvanen, 2001; Freimuth et al, 2003).

Pharmacogenomics includes studies of variations in germline DNA, somatic mutations and variations in RNA expression (Watters and McLeod, 2003). This minireview will focus on the impact of germline polymorphisms, highlighting their effects on the activity and response to commonly used chemotherapy drugs such as mercaptopurine, 5-fluorouracil, cyclophosphamide, platinum agents and camptothecins.

Thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT)

Perhaps the most compelling evidence for the utility of pharmacogenomic strategies to identify patients at risk for adverse drug reactions comes from genetic polymorphisms in the gene (TPMT). Mercaptopurine is a commonly used treatment for childhood acute lymphocytic leukaemia. Thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) methylates mercaptopurine, reducing its bioavailability for conversion into thioguanine nucleotides (TGN), the cytotoxic form of the drug. Approximately 10% of patients have an intermediate enzyme activity and 0.3% are deficient for TPMT activity. Intermediate-activity patients have a greater incidence of thiopurine toxicity, whereas TPMT-deficient patients have severe or fatal toxicity from mercaptopurine therapy. To date, at least 10 variations in the TPMT gene have been associated with low TPMT enzyme activity (McLeod and Siva, 2002). Three of these variants (TPMT*2, TPMT*3A and TPMT*3C) account for up to 95% of low TPMT activity phenotypes. Patients heterozygous for these alleles have intermediate TPMT levels and tolerate approximately 65% of standard mercaptopurine dosage (Relling et al, 1999b). Patients homozygous for the variant TPMT alleles are at high risk for severe, sometimes life-threatening toxicity, requiring significant reductions in drug doses (one out of 10 to one out of 15 of the standard dose). Patients requiring dose reduction because of variant TPMT alleles have similar or superior survival compared to patients with the wild-type allele (Relling et al, 1999a). TPMT*3A is the most common allele in Caucasian populations, with a frequency between 3.2 and 5.7%. TPMT*2 and TPMT*3C alleles are present in 0.2–0.8% of Caucasians. A significant variation in TPMT allele frequencies is seen among different world populations. TPMT*3A is the only variation found in Southwest Asians (1%), whereas all variant alleles in African populations are TPMT*3C (5.4–7.6%) (McLeod and Siva, 2002). Pretreatment knowledge of a patient's TPMT genotype status is now being used in major centres for dose optimisation, in order to reduce prospectively the likelihood of adverse drug reactions in children with ALL.

Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPYD)

5-Fluorouracil (5FU) is one of the most commonly administered chemotherapy agents, used in combination therapy for treatment of colorectal, breast, head/neck and other solid tumours. Over 80% of 5-FU is inactivated by dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD). Decreased DPD activity is associated with >four-fold risk of severe or fatal toxicity from standard doses of 5FU (Van Kuilenburg et al, 2002). To date, at least 20 polymorphisms in the DPD gene (DPYD) have been described (McLeod et al, 1998). However, many of these polymorphisms have not been definitively associated with altered DPD activity, and not all toxicity to 5FU from reduced DPD activity can be explained by the currently known DPYD polymorphisms. The most consistent data are for the allele DPYD*2A, a G>A splice site transition that causes skipping of exon 14. Patients heterozygous for this polymorphism have low DPD activity and toxicity to 5FU (Wei et al, 1996). However, the allele frequency for DPYD*2A in control populations appears to occur at a low frequency (approximately one out of 135 in Caucasians) (McLeod et al, 1998) and a more complete genotype–phenotype relationship study remains to be completed. Currently, the apparently high false-negative rate for DPYD as a predictor for severe 5FU toxicity (Collie-Duguid et al, 2000) restricts the testing of DPYD*2A to either research studies or as a component of a panel of oncology-related pharmacogenetic markers.

UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 (UGT1A1)

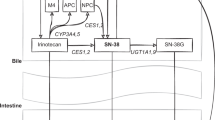

Irinotecan, a camptothecin analogue, is used to treat colorectal, lung and other solid tumours. 5FU/irinotecan combination therapy is a common front-line therapy for colorectal cancer. The active form of irinotecan, SN38, can be inactivated through glucuronidation by a member of the UDP-glucuronosyltransferase family. A dinucleotide repeat in a TATA box in the UGT1A1 promoter results in altered UGT1A1 activity (Monaghan et al, 1996). Reduced UGT1A1 is linked to a high risk (approximately four-fold) of severe toxicity from irinotecan treatment, including dose-limiting diarrhoea and neutropenia (Wasserman et al, 1997). The variable number of TA repeats ranges from five to eight copies, six TA repeats represent the most common allele, with up to 33% in Caucasians having a variant allele containing seven repeats (UGT1A1*28) (Iyer et al, 1999). Significant associations between patients with the UGT1A1*28 allele and reduced UGT1A1 expression, and, consequently, reduced SN38 glucuronidation have been shown in several studies (Ando et al, 1998; Iyer et al, 1999; Iyer et al, 2002). Assessment of the presence of the UGT1A1*28 allele in patients prior to irinotecan treatment may predict individuals at risk for severe toxicity from irinotecan, allowing the selection of lower doses or alternative therapies.

Glutathione S-Transferase P1 (GSTP1)

Glutathiones play a role in detoxifying, and consequently protecting cells from alkylating agents and products of reactive oxidation. The pi-class of human (GSTP1) has been found to catalyse glutathione conjugation of reactive metabolites from cyclophosphamide, a drug commonly used in the treatment of breast cancer and other solid tumours. In addition, GSTP1 is known to detoxify platinum compounds, including oxaliplatin, a relatively new chemotherapy drug used in combination with 5FU for the treatment of advanced colorectal cancer.

A SNP causes an isoleucine to valine substitution at amino-acid codon 105 (I105V) in the GSTP1 gene. The valine allele occurs at a frequency of 33% in Caucasian populations, and is associated with reduced GSTP1 activity compared to the isoleucine allele (Watson et al, 1998). This SNP has been correlated with response to cyclophosphamide chemotherapy treatment in breast cancer patients (Sweeney et al, 2000). In all, 240 patients treated with cyclophosphamide were characterised for the GSTP1 I105V SNP. Patients homozygous for the valine (low activity) allele had a 0.3 hazard ratio (95% confidence interval 0.1–1.0) for overall survival compared to patients homozygous for the isoleucine (high activity) allele. Patients heterozygous for the SNP had an intermediate hazard ratio for overall survival (0.8; 95% confidence interval 0.5–1.3) (Sweeney et al, 2000). In addition, a study of 107 patients with advanced colorectal cancer treated with a combination of 5FU and oxaliplatin were assessed for the GSTP1 I105V SNP (Stoehlmacher et al, 2002). Patients homozygous for the valine allele had a median of 24.9 months survival, compared to 7.9 months for patients homozygous for the isoleucine allele (P<0.001) (Stoehlmacher et al, 2002).

Currently, studies are mainly focused on the effect of SNPs in GSTP1 on the risk of cancer. Further research on the association of GSTP1 SNPs with response to alkylating agents and platinum drugs will provide information on the usefulness of prescreening patients for GSTP1 genotypes prior to treatment. In addition, genetic polymorphism in other genes involved in detoxification and repair have been associated with response or survival after platinum-containing chemotherapy (Park et al, 2001; Stoehlmacher et al, 2002), providing additional avenues for pharmacogenetic strategies to individualise therapy.

Thymidylate synthase (TYMS)

So far, this minireview has focused on the effects of polymorphisms in drug-metabolising enzymes in response to a range of chemotherapy drugs. Polymorphisms in drug targets are also an important area for pharmacogenetic studies, as overexpression or underexpression of drug targets could lead to resistance or toxicity to standard chemotherapy regimens.

The main target for 5-FU is thymidylate synthase (TS). Thymidylate synthase, together with a methyl cofactor, catalyses the methylation of dUMP to dTMP. The 5FU metabolite FdUMP forms a stable ternary complex with TS and the methyl cofactor, blocking the production of dTMP and ultimately inhibiting DNA synthesis. The overexpression of TS has been linked to resistance to 5-FU and other TS inhibitors, such as raltitrexed. Three polymorphisms have been described in the TS gene (TYMS). A polymorphic 28 bp tandem repeat in the promoter enhancer region (TSER) has been extensively characterised in multiple world populations (Marsh and McLeod, 2001a). The polymorphism varies from two (TSER*2) to nine (TSER*9) copies of the tandem repeat, with TSER*2 and TSER*3 being the most common alleles. The higher numbers of repeats are mainly found in African populations (Marsh et al, 2000), and their roles in TS expression are currently unknown. In vitro studies have demonstrated that TSER*3 has a higher TS expression than TSER*2 (Horie et al, 1995). In addition, small studies in cancer patients treated with 5FU have shown a correlation between TSER*3 and higher free TS protein levels (Kawakami et al, 1999), TSER*3 and reduced downstaging in rectal cancer (Villafranca et al, 2001) and TSER*3 and a lower response rate to 5FU treatment (Marsh et al, 2001b). In 2001, Villafranca and colleagues studied the TSER in 65 rectal cancer patients treated with chemoradiation. Over 60% of patients with at least one TSER*2 allele had downstaging of their rectal tumours (a marker of positive response to treatment), whereas only 22% of patients homozygous for TSER*3 had tumour downstaging (P=0.002) (Villafranca et al, 2001). Large-scale patient studies are now underway to better define the role of the TSER polymorphism to outcome from 5FU chemotherapy. However, a greater degree of resolution between ‘good’ and ‘poor’ outcome is needed to individualise therapy. It is likely that the TSER genotype would be used in conjunction with other TYMS variants and as part of a multiple gene panel in order to better individualise therapy.

A SNP has recently been described within the second repeat of the TSER*3 allele, which may also affect the level of TS expression in patients by abolishing a USF1-binding site (Mandola et al, 2003). Preliminary in vitro transfection assays have shown the common allele (denoted 3RG), which occurs in 56% of three repeat alleles in Caucasians (Mandola et al, 2003), to have a higher translational efficiency than all other TSER alleles (Kawakami and Watanabe, 2003). In addition, a study of 208 colorectal cancer patients and 675 controls found a 1.3-fold (95% confidence intervals 0.9–1.9) increased risk of colorectal cancer for patients with the 3RG allele, implying that the polymorphism may enhance the effects of the repeat polymorphism in the TSER (Stoehlmacher et al, 2003). A full functional analysis of this SNP, and a large-scale study in 5FU-treated patients, is now warranted.

A third polymorphism in the TYMS gene is a 6 bp deletion located in the 3′UTR, 447 bp downstream from the stop codon (Ulrich et al, 2000). The deletion is present at an allele frequency of 27% in Caucasians (Lenz et al, 2002). Recent data suggest a significant association of the deletion allele with a reduced response to 5FU-containing chemotherapy. Patients homozygous for the presence of the 6 bp sequence had an odds ratio of 2.0 for response to 5FU-containing combination chemotherapy (McLeod et al, 2003). A large-scale assessment of the role of each TYMS polymorphism individually and as a haplotype is now required to determine whether prospective assessment is warranted in patients prior to 5FU-containing chemotherapy treatment.

Polygenic pharmacogenomic strategies

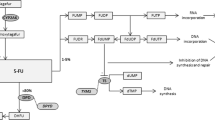

The examples highlighted in this review demonstrate the possible utility in prescreening patients for well-characterised polymorphisms to enable the best-tolerated and most effective treatment strategies to be identified. Unfortunately, genes do not act in isolation and drugs are often involved in complex metabolic pathways in the cell before they are converted to active or inactive forms. A clear example is seen with 5-FU, which utilises the cell's pyrimidine metabolic pathway (Figure 1). Variations in the DPYD gene can determine the amount of 5FU available for conversion to FdUMP, and variations in the TYMS gene can determine the amount of target available for inhibition by FdUMP. However, there are over 29 genes involved in the 5FU pathway (Figure 1), in which genetic variations in any or all can contribute to systemic toxicity or anti-tumour response. Initial steps are being taken to integrate drug pathway analysis, rather than single-gene studies, into clinical trials to assess the predictive power of chemotherapy activity and response. This will allow for the evaluation of gene–gene interactions in the context of anticancer drug effect. Drug pathway profiling in advance of therapy may allow us a greater chance to achieve the goal of optimising chemotherapy strategies. One can envision a future whereby comprehensive assessment of genetic variants in components of drug pathways for all approved anticancer drugs will be conducted at diagnosis. This would allow the selection of therapy that will be well tolerated and maximally efficacious. To enable this, a significant enhancement in our current understanding of the functional importance of the many genetic variants in drug pathway genes is required, in order to avoid the common finding of ‘polymorphism of unknown consequence’. Thus it is imperative that current active and planned clinical trials include correlative science components, in order to define clearly the relative contribution of pharmacogenetics to optimisation of chemotherapy.

5-Fuorouracil drug pathway demonstrating the interaction of multiple gene products. Genes discussed in this review are shown in bold. The official Human Genome Organization gene nomenclature is used. Common or alternative names for each gene can be found at http://pharmacogenetics.wustl.edu.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Ando Y, Saka H, Asai G, Sugiura S, Shimokata K, Kamataki T (1998) UGT1A1 genotypes and glucuronidation of SN-38, the active metabolite of irinotecan. Ann Oncol 9: 845–847

Collie-Duguid ES, Etienne MC, Milano G, McLeod HL (2000) Known variant DPYD alleles do not explain DPD deficiency in cancer patients. Pharmacogenetics 10: 217–223

Evans WE, McLeod HL (2003) Pharmacogenomics – drug disposition, drug targets, and side effects. N Engl J Med 348: 538–549

Freimuth RR, Ameyaw MA, Pritchard SC, Kwok PY, McLeod HL (2003) High-throughput genotyping methods for pharmacogenomic studies. Curr Pharmacogenom, In press

Horie N, Aiba H, Oguro K, Hojo H, Takeishi K (1995) Functional analysis and DNA polymorphism of the tandemly repeated sequences in the 5′-terminal regulatory region of the human gene for thymidylate synthase. Cell Struct Funct 20: 191–197

Iyer L, Das S, Janisch L, Wen M, Ramirez J, Karrison T, Fleming GF, Vokes EE, Schilsky RL, Ratain MJ (2002) UGT1A1*28 polymorphism as a determinant of irinotecan disposition and toxicity. Pharmacogenomics J 2: 43–47

Iyer L, Hall D, Das S, Mortell MA, Ramirez J, Kim S, Di Rienzo A, Ratain MJ (1999) Phenotype–genotype correlation of in vitro SN-38 (active metabolite of irinotecan) and bilirubin glucuronidation in human liver tissue with UGT1A1 promoter polymorphism. Clin Pharmacol Ther 65: 576–582

Kawakami K, Omura K, Kanheira E et al (1999) Polymorphic tandem repeats in thymidylate synthase gene is associated with its protein expression in human gastrointestinal cancers. Anticancer Res 19: 3249–3252

Kawakami K, Watanabe G (2003) Functional analysis of a novel single nucleotide polymorphism in the repeat-length polymorphism of thymidylate synthase gene. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res 44: 1071

Kwok PY (2001) Methods for genotyping single nucleotide polymorphisms. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2: 235–258

Lenz H-J, Zhang W, Zahedy S, Gil J, Yu M, Stoehlmacher J (2002) A 6 base-pair deletion in the 3 UTR of the thymidylate synthase (TS) gene predicts TS mRNA expression in colorectal tumors. A possible candidate gene for colorectal cancer risk. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res 43: 660

Mandola MV, Stoehlmacher J, Muller-Weeks S, Cesarone G, Groshen S, Tsao-Wei DD, Lenz H-J, Robert Ladner D (2003) A novel SNP within the tandem repeat polymorphism of the thymidylate synthase gene abolishes USF-1 binding and predicts outcome of metastatic colorectal carcinoma treated with 5-fluorouracil. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res 44: 597

Marsh S, Ameyaw MM, Githang'a J, Indalo A, Ofori-Adjei D, McLeod HL (2000) Novel thymidylate synthase enhancer region alleles in African populations. Hum Mutat 16: 528

Marsh S, Kwok P, McLeod HL (2002) SNP databases and pharmacogenetics: great start, but a long way to go. Hum Mutat 20: 174–179

Marsh S, McKay JA, Cassidy J, McLeod HL (2001b) Polymorphism in the thymidylate synthase promoter enhancer region in colorectal cancer. Int J Oncol 19: 383–386

Marsh S, McLeod HL (2001a) Thymidylate synthase pharmacogenetics in colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 1: 175–178

McLeod HL, Collie-Duguid ES, Vreken P, Johnson MR, Wei X, Sapone A, Diasio RB, Fernandez-Salguero P, van Kuilenberg AB, van Gennip AH, Gonzalez FJ (1998) Nomenclature for human DPYD alleles. Pharmacogenetics 8: 455–459

McLeod HL, Sargent DJ, Marsh S, Fuchs CS, Ramanathan RK, Williamson SK, Findlay BP, Thibodeau SN, Petersen GM, Goldberg RM (2003) Pharmacogenetic analysis of systemic toxicity and response after 5-fluorouracil (5FU)/CPT-11, 5FU/oxaliplatin (oxal), or CPT-11/oxal therapy for advanced colorectal cancer. Proc Am Assoc Clin Oncol 22: 252

McLeod HL, Siva C (2002) The thiopurine S-methyltransferase gene locus – implications for clinical pharmacogenomics. Pharmacogenomics 3: 89–98

Monaghan G, Ryan M, Seddon R, Hume R, Burchell B (1996) Genetic variation in bilirubin UPD-glucuronosyltransferase gene promoter and Gilbert's syndrome. Lancet 347: 578–581

Park DJ, Stoehlmacher J, Zhang W, Tsao-Wei DD, Groshen S, Lenz HJ (2001) A Xeroderma pigmentosum group D gene polymorphism predicts clinical outcome to platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 61: 8654–8658

Relling MV, Hancock ML, Boyett JM, Pui CH, Evans WE (1999a) Prognostic importance of 6-mercaptopurine dose intensity in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 93: 2817–2823

Relling MV, Hancock ML, Rivera GK, Sandlund JT, Ribeiro RC, Krynetski EY, Pui CH, Evans WE (1999b) Mercaptopurine therapy intolerance and heterozygosity at the thiopurine S-methyltransferase gene locus. J Natl Cancer Inst 91: 2001–2008

Sachidanandam R, Weissman D, Schmidt SC, Kakol JM, Stein LD, Marth G, Sherry S, Mullikin JC, Mortimore BJ, Willey DL, Hunt SE, Cole CG, Coggill PC, Rice CM, Ning Z, Rogers J, Bentley DR, Kwok PY, Mardis ER, Yeh RT, Schultz B, Cook L, Davenport R, Dante M, Fulton L, Hillier L, Waterston RH, McPherson JD, Gilman B, Schaffner S, Van Etten WJ, Reich D, Higgins J, Daly MJ, Blumenstiel B, Baldwin J, Stange-Thomann N, Zody MC, Linton L, Lander ES, Altshuler D (2001) A map of human genome sequence variation containing 1.42 million single nucleotide polymorphisms. Nature 409: 928–933

Shi MM (2001) Enabling large-scale pharmacogenetic studies by high-throughput mutation detection and genotyping technologies. Clin Chem 47: 164–172

Stoehlmacher J, Mandola MV, Yun J, Sones E, Zhang W, Gil J, Mallik N, Park DJ, Yu MC, Ladner RD, Lenz H-J (2003) Alterations of the thymidylate synthase (TS) pathway and colorectal cancer risk – the impact of three TS polymorphisms. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res 44: 597

Stoehlmacher J, Park DJ, Zhang W, Groshen S, Tsao-Wei DD, Yu MC, Lenz HJ (2002) Association between glutathione S-transferase P1, T1, and M1 genetic polymorphism and survival of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 94: 936–942

Sweeney C, McClure GY, Fares MY, Stone A, Coles BF, Thompson PA, Korourian S, Hutchins LF, Kadlubar FF, Ambrosone CB (2000) Association between survival after treatment for breast cancer and glutathione S-transferase P1 Ile105Val polymorphism. Cancer Res 60: 5621–5624

Syvanen AC (2001) Accessing genetic variation: genotyping single nucleotide polymorphisms. Nat Rev Genet 2: 930–942

Ulrich CM, Bigler J, Velicer CM, Greene EA, Farin FM, Potter JD (2000) Searching expressed sequence tag databases: discovery and confirmation of a common polymorphism in the thymidylate synthase gene. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 9: 1381–1385

Van Kuilenburg AB, Meinsma R, Zoetekouw L, Van Gennip AH (2002) High prevalence of the IVS14+1G>A mutation in the dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase gene of patients with severe 5-fluorouracil-associated toxicity. Pharmacogenetics 12: 555–558

Villafranca E, Okruzhnov Y, Dominguez MA, Garcia-Foncillas J, Azinovic I, Martinez E, Illarramendi JJ, Arias F, Martinez Monge R, Salgado E, Angeletti S, Brugarolas A (2001) Polymorphisms of the repeated sequences in the enhancer region of the thymidylate synthase gene promoter may predict downstaging after preoperative chemoradiation in rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 19: 1779–1786

Wasserman E, Myara A, Lokiec F, Goldwasser F, Trivin F, Mahjoubi M, Misset JL, Cvitkovic E (1997) Severe CPT-11 toxicity in patients with Gilbert's syndrome: two case reports. Ann Oncol 8: 1049–1051

Watson MA, Stewart RK, Smith GB, Massey TE, Bell DA (1998) Human glutathione S-transferase P1 polymorphisms: relationship to lung tissue enzyme activity and population frequency distribution. Carcinogenesis 19: 275–280

Watters JW, McLeod HL (2003) Cancer pharmacogenomics: current and future applications. Biochim Biophys Acta 1603: 99–111

Wei X, McLeod HL, McMurrough J, Gonzalez FJ, Fernandez-Salguero P (1996) Molecular basis of the human dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency and 5-fluorouracil toxicity. J Clin Invest 98: 610–615

Wiffen P, Gill M, Edwards J, Moore A (2002) Adverse drug reactions in hospital patients: a systematic review of the prospective and retrospective studies. Bandolier Extra http://www.jr2.ox.ac.uk/bandolier/extra.html

Acknowledgements

Work in the authors laboratory was supported in part by the NIH Pharmacogenetics Research Network (U01 GM63340). Additional drug pathways can be viewed at http://pharmacognetics.wustl.edu

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Marsh, S., McLeod, H. Cancer pharmacogenetics. Br J Cancer 90, 8–11 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6601487

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6601487

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Impact of GSTM1, GSTT1 and GSTP1 gene polymorphism and risk of ARV-associated hepatotoxicity in HIV-infected individuals and its modulation

The Pharmacogenomics Journal (2017)

-

Predictive assessment in pharmacogenetics of XRCC1 gene on clinical outcomes of advanced lung cancer patients treated with platinum-based chemotherapy

Scientific Reports (2015)

-

XRCC1 and GSTP1 polymorphisms and prognosis of oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis

Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology (2013)

-

A phase II trial of erlotinib in combination with gemcitabine and capecitabine in previously untreated metastatic/recurrent pancreatic cancer: combined analysis with translational research

Investigational New Drugs (2012)

-

Expressions of thymidylate synthase, thymidine phosphorylase, class III β-tubulin, and excision repair cross-complementing group 1 predict response in advanced gastric cancer patients receiving capecitabine plus paclitaxel or cisplatin

Chinese Journal of Cancer Research (2011)