Abstract

Lung cancer is recognized as a leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide and its frequency is still increasing. The prognosis in lung cancer is poor and limited by the difficulties of diagnosis at early stage of disease, when it is amenable to surgery treatment. Therefore, the advance in identification of lung cancer genetic and epigenetic markers with diagnostic and/or prognostic values becomes an important tool for future molecular oncology and personalized therapy. As in case of other tumors, aberrant epigenetic landscape has been documented also in lung cancer, both at early and late stage of carcinogenesis. Hypermethylation of specific genes, mainly tumor suppressor genes, as well as hypomethylation of oncogenes and retrotransposons, associated with histopathological subtypes of lung cancer, has been found. Epigenetic aberrations of histone proteins and, especially, the lower global levels of histone modifications have been associated with poorer clinical outcome in lung cancer. The recently discovered role of epigenetic modifications of microRNA expression in tumors has been also proven in lung carcinogenesis. The identified epigenetic events in lung cancer contribute to its specific epigenotype and correlated phenotypic features. So far, some of them have been suggested to be cancer biomarkers for early detection, disease monitoring, prognosis, and risk assessment. As epigenetic aberrations are reversible, their correction has emerged as a promising therapeutic target.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nowadays it is clearly acknowledged, that during neoplastic transformation genetic lesions are accompanied by equally important epigenetic modifications. The altered methylation pattern of promoter sequence can cause the same effect as the mutation in coding region of the gene and may be subject to the same processes of selection as genetic changes during carcinogenesis [1, 2]. What’s more, the mutual interaction between the two mechanisms—genetic and epigenetic—has been confirmed [3–5]. Epigenetic modifications may lead to point mutations, as in case of epigenetically silenced DNA repair genes, and conversely, genetic mutations can disturb normal methylation pattern [6, 7]. Additionally, it has been observed that epigenetic modifications are much more diverse and frequent than DNA mutations [1, 3, 8].

Epigenetic mechanisms, related to inherited changes in gene expression without alterations in the primary DNA sequence [8, 9], are essential for normal cellular functioning. They play particularly important role in genome activity regulations, encompassing key biological processes, such as differentiation and embryonic development, tissue-specific gene expression regulation or imprinting and X chromosome silencing in females. Epigenetic mechanisms comprise DNA methylation, histone modifications, nucleosome positioning, and small, noncoding RNAs (miRNA, siRNA) regulation. During the last few decades, epigenetic alterations are widely described as essential players in cancer development and progression [10]. Epigenetic changes have been identified as putative cancer biomarkers for early detection, cancer management and monitoring, as well as disease prognosis, and risk assessment.

As so far, the best known epigenetic modifications observed in human tumor cells are aberrant DNA methylation patterns—the first epigenetic alterations identified in cancer—and nucleosomal histone modifications. The first articles on this subject were published in 1980s. The subsequent studies showed that the spatial conformation of chromatin, associated with nucleosome positioning, also affects gene expression. Recently, the role of non-coding RNA (ncRNA) in the epigenetic control has been described. Publications regarding this level of epigenetic signature have appeared during the last 4 years. So, the molecular mechanisms underlying epigenetic regulatory processes have been discovered relatively recently, and the knowledge of this field is still enriched. The most frequent epigenetic modifications in cancer cell and the involved mechanisms are summarized in Table 1.

The final result of epigenetic modifications, listed in Table 1, is the altered structure of chromatin involved in packaging of the human genome. This process, the so called chromatin remodeling, is associated with chromatin conformational changes into functionally active structure (euchromatin) or inactive condensed form (heterochromatin) [1, 11, 12]. The additional epigenetic level in gene expression control is carried out by deregulation of non-coding RNA function and post-transcriptional miRNA control of 3′untranslated regions (3′UTR) of target messenger RNAs via transcript destabilization and mRNAs repression and/or inhibition of translation [13].

Although cancer is traditionally regarded as genetic disorder, it has been thoroughly documented that epigenetic changes are very powerful modulators of cellular phenotype in pathological mechanism of carcinogenesis. Figure 1 depicts molecular changes—both genetic and epigenetic—during lung carcinogenesis.

The effect of epigenetic modifications on gene expression

It is well documented that the presence of methylated cytosines in CpG islands within gene promoter sequence prevents binding of the transcription machinery or allows binding of transcription repressors [8, 10, 14]. So, the effect of DNA methylation is gene silencing related to the inhibition of its transcription. In case of histone modifications, their activating/inhibiting influence on gene transcription depends upon the localization of modified amino acid and specific core histone, the so called “histone code” [15, 16]. Particularly important are the N-terminal modifications of histones H3 and H4. For example, acetylation of lysine 4 in histone H3 (H3K4) enables active gene transcription, and its deacetylation results in gene silencing [15, 17–19]. Regarding methyl group binding to the histones, trimethylation of H3K4 (H3K4me3) is observed in transcriptionally active chromatin, while trimethylation of lysine 27 in H3 (H3K27me3) has suppressive effect [15, 17, 19, 20].

Both DNA methylation and histone modifications are enzymatic processes and are reversible. The enzymes participating in histone modifications are histone acetyltransferases (HATs), histone methyltransferases (HMTs), histone deacetylases (HDACs) and histone demethylases (HDMs) [8, 17, 19]. DNA methylation is mediated by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs). In human, there are three catalytically active DNMT forms (DNMT1, DNMT3A, DNMT3B). DNMT1 is responsible for maintaining the existing pattern of methylation, while DNMT3A and 3B mediate de novo methylation [12, 21, 22]. Methylated promoter sequence is recognized by methyl binding proteins (MBPs), including MeCP2 (methyl CpG binding protein 2), MBD1 (methyl-CpG binding domain protein 1) and ZBTB 33 (zinc finger and BTB domain containing protein 33; KAISO). These proteins form complexes with transcriptional co-repressors (CRs), as well as HDACs and HMTs [4, 15, 23, 24]. This indicates that these epigenetic processes—DNA methylation and histone modifications—are tightly interrelated, and co-operate in gene expression regulation [1, 12, 15, 18, 20, 25–27]. There are evidences of direct influence of DNA methylation on histone modifications, as well as the effect of histone modifications on de novo DNA methylation [8, 11, 15, 28]. Still, the open question remains which of them occurs first. The results of many research works suggest the opposite findings [26, 28].

Additionally, very recently, it has been discovered that not only protein-coding genes but also micro-RNAs, possessing growth inhibitory function, could be epigenetically silenced in cancer cells [29]. According to the results of analysis of genomic sequences of miRNA genes, approximately half of miRNAs are associated with CpG islands [30], suggesting that the epigenetic events can influence also miRNA expression. This is also confirmed by the findings, that some miRNAs are upregulated when (i) the cells are exposed to the demethylating agents, such as 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine, (ii) when mutation of DNMT is present or (iii) upon histone deacetylase inhibitor treatment [29, 31, 32]. Epigenetic silencing of miRNAs results in down- or up-regulation of their targets, i.e., tumor suppressor genes or oncogenes of known function in carcinogenesis.

Altered DNA methylation pattern in carcinogenesis

More than 20 years ago it was found that DNA methylation patterns in cancer cells—in comparison to normal cells—are altered [4, 23, 33]. Methylation analysis of more than 1000 non-selected CpG islands in various primary tumors (e.g., breast, colon, testis, head and neck carcinoma) confirmed disturbed methylation patterns [34]. These alterations involve global genome hypomethylation concerning normally methylated sequences and/or hypermethylation of CpG reach sequences (CpG islands) in promoters of tumor suppressor genes (TSGs) which remain unmethylated under normal conditions [1, 5, 6, 23, 35, 36].

DNA hypomethylation leads to carcinogenesis via three molecular mechanisms: (1) microsatellite instability through activation of repetitive elements (SINE or LINE) or retrotransposons (2) transcriptional activation and overexpression of oncogenes (3) loss of imprinting (LOI) [4, 6, 37, 38].

Global DNA hypomethylation is characteristic for neoplastic transformation from benign to malignant tumors and is known to be increased with cancer progression [37, 39]. On the other hand, regional hypermethylation of TSGs is observed in many human types of cancer, including lung, and plays important role in carcinogenesis [1, 15, 39–46]. These processes—hypo- and hypermethylation—are often observed in parallel in cancer cell, however they are recognized as independent epigenetic changes and are linked with different DNA sequences [23, 35, 37].

TSGs regulate many physiological processes in cell, such as growth, proliferation and apoptosis. They also code for transcriptional factors, adhesion molecules, proteins which regulate angiogenesis as well as participate in DNA repairing system, cell cycle regulation including cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors and GTP-ase activators [1, 8, 26]. Epigenetic alteration of TSGs involved in regulation of cell cycle may disturb the main cell signaling pathways responsible for regulation of proliferation and apoptosis, while promoter hypermethylation of DNA repair genes prevents DNA repair process and results in accumulation of genetic instability in transforming cell, initiating carcinogenesis [7, 8].

Epigenetic silencing of TSGs is an early event in carcinogenesis. The results of many studies indicate that it is observed also in benign tumors, as well as during early neoplastic progression [1, 23, 36, 40, 47–56]. On the other hand, the aberrant DNA methylation pattern significantly correlates with poorer tumor differentiation, higher malignancy and worse prognosis in a patient. It clearly indicates that DNA methylation increases during cancer progression [40, 47–49, 53, 54, 56].

The proposed model of CIMP (CpG island methylator phenotype) explains cancer development through the simultaneous inactivation of multiple genes, both TSGs and DNA repair genes, as well as including MSI events. The authors of the hypothesis suggested that it could be true for many types of cancer [57]. Indeed, the recent studies, concerning among others stomach cancer, breast cancer and non-small cell lung carcinoma, have indicated CIMP as independent prognostic factor [58–60].

Altered histone modifications in carcinogenesis

Nucleosomal histones are targets of a large number of post-translational modifications, including methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, glycosylation, ADP-ribosylation and sumoylation (see Table 1), among which acetylation has been the most extensively investigated [61], confirming the links to cancer initiation and progression. This modification is dynamically preserved in vivo by the opposing histone acetyltransferase (HAT) and deacetylase (HDAC) actions [62].

Unstructured N-terminal tails (20–30 residues) of core histones (H2A, H2B, H3, H4) contain multiple lysine residues for covalent modifications, including acetylation. Each core histone contains different variants and acetylation occurs on many of them. However, it has been recognized that histone acetylation does not act alone but actively cross-talks with other histone modifications, as well as with DNA methylation [63]. Histone acetylation and DNA methylation are known to be intimately linked, as mediated by a group of proteins with methyl-binding activity (the above mentioned KAISO, MBD1 and MeCP2) which—after binding to the methylated gene promoters—recruit protein complexes that contain HDACs thereby leading to gene silencing and chromatin condensation.

In normal cells, the non-disturbed histone acetylation pattern (belonging to the above mentioned histone code) controls many cellular and developmental processes, including gene expression, DNA replication, DNA repair or DNA recombination [17]. Thus, the abnormal histone acetylation leads to cancer development via affecting many nuclear and cellular processes [17, 64]. Moreover, disruption of enzyme activities, i.e., HAT or HDACs, may play a significant role in uncontrolled growth and proliferation of tumor cells. The study results have shown that treatment with HDAC inhibitor (trichostatin A, TSA) via increasing histone acetylation results in increased expression of many genes encoding suppressors of invasion and metastasis, negative cell-cycle regulators and apoptosis-related proteins [65].

In addition to changes in histone acetylation, cancer cells are also distinguished by widespread changes in histone methylation patterns. The polycomb repressor complex 2 (PRC2)—which is recognized as a significant functional component for polycomb group gene family—is involved in the initiation of silencing and contains histone methyltransferases that can methylate histone H3 lysine 9 and 27, which are marks of silenced chromatin. The polycomb gene BMI1, a component of PRC1, is overexpressed in several human cancers so that it might be expected that aberrations in this system would give rise to global alterations in gene silencing in cancer [66]. The results of experimental studies indicate the increased level of repressive polycomb mark trimethylated H3K27 in cancer cells relative to a normal cells, resulting in histone modification and target gene silencing [67].

The rapidly emerging data strongly indicate that the entire epigenome is fundamentally disturbed in cancer development. Moreover, these genome-wide changes in the structure of the epigenome can lead to the genomic instability, that is a hallmark of cancer [68]. Accumulating evidence clearly indicates fundamental association between global histone modification levels and tumor aggressiveness, regardless of cancer type [69].

Epigenetically altered micro-RNA regulation in carcinogenesis

Micro-RNAs are small non-coding RNAs of ~22 nucleotides length. Based on the degree of homology to their 3′UTR target sequence, miRNAs can induce translational repression or degradation of target mRNAs. Although, it has been also described that miRNAs can also increase the expression of mRNA [70]. In human genome, it is estimated that 1,000 miRNAs are transcribed and 30 % of all genes are under miRNA regulation, so one miRNA modulates hundreds of downstream genes via post-transcriptional process. Thus, miRNAs control a wide range of biological processes, including cell development, proliferation and differentiation, as well as apoptosis [71].

As miRNAs play significant roles in the normal functioning of the cells, their deregulation would result in disruption of normal cell functions and lead to diseases as well. Indeed, in many types of human cancer the study results indicate aberrant miRNAs expression—both overexpression and downregulation [72, 73]. Thus, and according to the target mRNAs, miRNAs have been proposed to function as either tumor suppressors or oncogenes.

Similarly like in case of protein-coding genes associated with cancer, the most convincing evidence linking miRNAs to tumorigenesis comes from genetic alterations in cancer cells. Genetic mechanisms leading to the deletion, amplification, or translocation of miRNAs are usually chromosomal abnormalities. Especially, approximately 50 % of human miRNA genes are located at fragile sites or areas of the genome which are prone to breakage and rearrangement in cancer cells. The examples are two tumor-suppressor microRNAs, miR-15a and miR-16-1, that are down-regulated in 70 % of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cases due to chromosomal deletions or mutations at their loci [74]. Also, factors involved in miRNA biosynthesis machinery are dysregulated in human tumors [75].

The results of several studies revealed that miRNAs are also under epigenetic regulation. As mentioned earlier, nearly half of miRNAs are associated with CpG islands, making them prone to epigenetic modifications. It has been proven by the findings that some miRNAs are up-regulated upon the exposure of cells to the agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine, or upon mutation of methyltransferases (DNMTs) [29, 31]. Indeed, several miRNAs have been identified that are silenced by CpG hypermethylation in cancer cells, as compared to normal ones. For example, miR-203 frequently undergoes DNA methylation in T cell lymphoma, but not in normal T lymphocytes [76]. Hypermethylated miRNAs have been discovered in several types of cancer, including breast (especially miR-9-1, but also: mir-124a3, mir-148, mir-152, and mir-663) [31], colorectal (miR-124a, miR-43b, miR-34c) [29, 77], oral (miR-137, miR-193a) [78], bladder and prostate tumors (miR-126) [79] or hepatocellular carcinoma (miR-124, miR-203, miR-375) [80]. Epigenetic regulation of miRNA activity is a very cell- and tumor type-specific. An example is let-7a-3 which has been found to be hypermethylated in breast cancer [31], but hypomethylated in lung cancer [81].

Additionally, in cancer cells, not only DNA methylation status but also chromatin structure around miRNA genes differ between cancer and normal cells, as demonstrated in several studies. In bladder cancer Saito et al. [82] revealed, that DNA demethylation and histone deacetylase inhibition could reverse miR-127 expression in cancer cells. Similarly, in the study performed by Bandres et al. [83], treatment with a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor and a HDAC inhibitor restored expression of 3 of the 5 microRNAs (hsa-miR-9, hsa-miR-129 and hsa-miR-137) in colorectal cancer cell lines.

In summary, emerging evidences suggest that epigenetic changes of miRNA represent another mechanism that plays a role in carcinogenesis, resulting in down- or up regulation of the protein product of the target mRNAs. Especially, having in mind that among miRNA target genes are oncogenes, tumor suppressor genes, multiple cell cycle regulators, including cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinases, Rb-family proteins, and Cip/Kip family of cell-cycle inhibitors, antiapoptotic genes, and key sets of genes involved in invasion and migration, as well as those engaged in angiogenesis [84]. The number of the identified epigenetically altered miRNAs is still growing and their function is being elucidated. Although, in many cases, the prediction of specific targets remains a major bio-informatic challenge and future studies will therefore have to address the identification of target mRNAs and the elucidation of the functional consequences of deregulated miRNAs. Table 2 lists examples of miRNAs that undergo epigenetic modifications in human cancers and their target genes.

So far, many reports have revealed abnormal microRNA expression in cancer cells, clearly suggesting that it is not an exception, but the rule, in human cancer. Indeed, an aberrant microRNA profiling (miRNome) has been described in almost all human cancers, and could be applied as useful marker for tumor classification, diagnosis, and prognosis.

Epigenetics in lung cancer

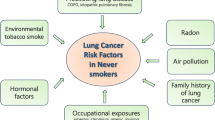

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide [85, 86]. Although lung cancer diagnoses in men decreases each year and death rates also decline, the incidence of this type of cancer in women increases by 0.5 % each year. Lung cancer in women, as compared with men, occurs at a slightly younger age, and almost half of lung cancer cases in patients under 50 years old occurs in women, even in those who have never smoked. The reason for this is not completely understood. Although cigarette smoking is the primary cause of the increased incidence of lung cancer in women and men, some other etiologic factors, like exposure to secondhand smoke, asbestos, radon or heavy metals also plays some role [86]. Additionally some genetic factors (involving genes which participate in carcinogen metabolism, cell growth control, DNA repair system) and hormones such estrogen (in women) could directly or indirectly affect cancer growth and might contribute to the development of this type of cancer. Five year survival after lung cancer surgery is approximately 10–70 % depending on the stage of the tumor [87].

Primary lung cancer originates from epithelial cell. Four basic histological types are distinguished, representing approximately 95 % of all lung cancers. These are: Squamous Cell Carcinoma/SCC/(40 %), Adenocarcinoma/AC/(30 %) and Large Cell Cancer/LCC/(10 %) belonging to Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma (NSCLC), and Small Cell Carcinoma (SCLC). Squamous Cell Carcinomas are associated with cigarette smoking, adenocarcinomas may be found in patients who have never smoked.

Because of treatment concerns, lung cancers are separated into two groups: Non- Small Cell Lung Carcinoma (NSCLC) which accounts for approximately 80 % of all primary lung cancers and Small Cell Lung Carcinoma (SCLC) which accounts for 20 % [86]. NSCLCs are relatively insensitive to chemotherapy and radiation therapy compared with SCLCs. Patients with resectable lesion may be cured by surgery or surgery followed by chemotherapy. Local control using radiation therapy can be achieved in a large number of patients with unresectable disease, but cure is achieved only in a small number of patients. SCLC differs from other histological types in terms of many biological and clinical characteristics (high rates of proliferation, short doubling time of tumor mass, a prominent tendency to early hematogenous spread, chemo- and radiosensitivity) [86].

Epigenetic changes observed in lung carcinogenesis include the three main aberrations: aberrant DNA methylation pattern (hyper- and hypomethylation), histone modifications and non-coding RNA regulation.

DNA hypomethylation in lung carcinogenesis

Hypomethylation in lung cancer tissue is manifested by: (i) demethylation of the promoter regions of oncogenes; (ii) reduced global amount of methylcytosines in the genome; (iii) demethylation of repetitive DNA, which under physiological conditions is heavily methylated; (iv) increased transcription of the mobile elements of the genome (transposons)—e.g., LINE sequences—and the associated increase in mitotic recombination leading to deletions and translocations.

Aberrant methylation pattern, mainly global hypomethylation of CpG regions, is a hallmark of many cancers, including lung cancer [88]. Global demethylation generally occurs during initiation and progression of cancerogenesis, but in many cases it does not depend on the level of tumor development. Additionally, the results of some studies indicate the significance of not the total demethylation level of the genome but rather of where the hypomethylation is focused in the genome and what genes are affected [89].

So far only a few studies have analyzed global hypomethylation process in primary cancers with the aim of exploring its clinical importance as a molecular marker [90–92].

Long interspersed element (LINE), an abundant class of retrotransposons, occupying nearly 17 % of the human genome, provides a surrogate marker for global hypomethylation [93, 94]. Hypomethylation within the promoter region of potent LINE-1 sequence causes transcriptional activation of LINE-1, resulting in transposition of the retro-element and chromosomal alteration. LINE-1 methylation status may therefore be a key factor linking global hypomethylation with genomic instability which can lead to the progression of cancerogenesis [95–97]. The association between LINE-1 methylation and genomic instability also suggests that it may be a good prognostic marker in cancer, as previous studies have reported associations between genomic instability and the outcome of cancer patients [97].

Regarding lung carcinoma, LINE-1 hypomethylation was found as an independent marker of poor prognosis in stage IA NSCLC. The results revealed that tumor LINE-1 methylation status may help to select early-stage NSCLC patients requiring adjuvant treatment after curative surgery [98].

Recently, Daskalos et al. [99] have examined the protein related to the p53 tumor protein—TP73 or p73. This protein is involved in cellular stress response and development, cell cycle regulation, and induction of apoptosis. It possesses an intrinsic P2 promoter, controlling the expression of the pro-apoptotic TAp73 isoform and the anti-apoptotic ΔΝp73 isoform. In the studied primary NSCLC samples, the researchers demonstrated the P2 hypomethylation of p73 protein and the associated over-expression of ΔΝp73 mRNA. They found it as a frequent event, particularly in SCCs. Interestingly, P2 hypomethylation strongly correlated with LINE-1 element hypomethylation, indicating that ΔΝp73 over-expression might be a passive consequence of global DNA hypomethylation.

In NSCLC samples the coordinated promoter demethylation of cancer/testis antigens (CTAs)—the potential, novel candidate proto-oncogenes—associated with their upregulation was also found [100]. These genes are expressed in germline cells and in many tumors, but not in normal somatic tissue, apart from testis and placenta. As the study results indicate, CTA expression is tightly associated with a squamous cell histology, and not with lung adenocarcinoma. The coordinated regulation of CTAs and related target genes, like MAGEA, SBSN, TKTL-1, ZNF711, G6PD, has been found to have epigenetic background, correlated with demethylation process. So far, SBSN, ZNF-711 and G6PD have not been associated with tumor specific expression or carcinogenesis.

TKTL1, encoding a transketolase-like enzyme, has been found recently as a new and independent predictor of survival in patients with NSCLC. Since inhibition of transketolase enzyme activity has recently been shown to effectively suppress tumor growth, TKTL1 may represent a novel pharmacodiagnostic marker [101].

Another member of the cancer/testis antigen family, BORIS (brother of the regulator of the imprinted site, alternative symbols CTCFL; CCCTC-binding factor-like protein) is an 11 zinc finger (ZF) protein, which is considered to be a new oncogene. BORIS presents a uniquely paired set of genes which dysfunctions may contribute to development of multiple tumor types via epigenetic reprogramming at CTCF target sites, influencing many cell proliferation-associated genes. It has been documented that human BORIS is not only aberrantly activated in many types of human cancers, but also maps to the cancer-associated amplification region at 20q13 [102]. Normally, this gene is expressed only in germ cells, but is also aberrantly activated in numerous cancers [102, 103]. The expression of BORIS gene is controlled predominantly by changes in DNA-methylation, as its activation requires promoter demethylation. In many types of human cancer, high expression of BORIS protein correlates with the tumor size and grade. Silencing of BORIS induces apoptosis in tumorous cell lines [104]. In lung carcinoma cell lines, expression of this gene varies from high to moderate levels [104, 105]. This, in turn, is correlated with the level of BORIS promoter methylation [104]. Additionally, BORIS positively regulates some of the CTAs by binding and inducing a shift to a more open chromatin conformation with promoter hypomethylation of MAGEA3, or independently of promoter hypomethylation in case of MAGEA2 and MAGEA4 and thus may be a key effector involved in their de-repression in lung cancer [106]. Additionally, in lung cancer cells the activity of CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF), which influences Rb2/p130 gene expression is decreased by BORIS, therefore may correlate with progression of lung tumors [107].

The 14-3-3 proteins form a set of seven highly conserved proteins that have recently been implicated in human tumorigenesis. One isoform of the 14-3-3 family, 14-3-3sigma (14-3-3σ), plays a crucial role in G2 checkpoint by sequestering Cdc2-cyclinB1 in the cytoplasm. Radhakrishnan et al. [108] found that the expression level of 14-3-3σ was elevated in the majority of the studied human NSCLC tissues. The gene was hypomethylated in lung tumors as compared with normal lung tissue. This suggests that decreased DNA methylation results in increased expression of 14-3-3σ in NSCLC. There are findings that chemotherapy resistance in NSCLC may also be increased with increased expression of 14-3-3σ via interaction with IGF-1. It has been documented that IGF-1R inhibitors may increase the efficacy of chemotherapy, particularly in SCC [109].

Another observation concerns thymosin β(10) (TMSB10). It is a monomeric sequestering protein that regulates actin cytoskeleton organization. TMSB10 hypomethylation, leading to its overexpression, is a quite frequent event in NSCLC, but probably it is not a common mechanism underlying the gene overexpression [88]. In lung cancer, overexpression of TMSB10 was correlated with several unfavorable clinicopathological characteristics. What is more, thymosin β(10) is thought to induce microvascular and lymphatic vessel formation by up-regulating vascular endothelial growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor-C in lung cancer tissues, thus promoting the distant and lymph node metastases and being implicated in the progression of NSCLC [110].

The findings regarding hypomethylation in the above-mentioned genes and their feasibility as diagnostic and prognostic marker are summarized in Table 3.

DNA hypermethylation in lung carcinogenesis

As mentioned earlier, hypermethylation of gene promoters is often associated with transcriptional silencing of tumor suppressors. It is believed that this process leads to the initiation and progression of carcinogenesis [111]. Numerous studies have suggested possible clinical usefulness of promoter hypermethylation as marker of early diagnosis and as predictor of patient outcome in lung cancer. There are several studies suggesting various marker panels for lung cancer identification and differentiation.

Kwon et al. [112] have proposed six genes (CCDC37, CYTL1, CDO1, SLIT2, LMO3, and SERPINB5) for lung squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) identification. Especially, methylation pattern of CYTL1 promoter region was significantly different between early and advanced stages of SCCs. Shames et al. [44] examined seven potential lung cancer markers (ALDH1A3, BNC1, CCNA1, CTSZ, LOX, MSX1 and NRCAM), three of which showed frequent tumor-specific hypermethylation as compared with normal tissue. In the study performed by Cortese et al. [113] four genes (FGFR3, LAPTM5, MDK, MEOX2) were identified as aberrantly methylated in lung cancer. MEOX2 was uniformly higher methylated in all lung cancer samples, while the methylation of the other three genes was correlated with either the differentiation status of the tumor (MDK, LAPTM5) or with the tumor histopathological type (FGFR3). Another panel of markers for diagnostic application in lung cancer, elucidated recently by Begum et al. [114], consists of six most promising genes (APC, CDH1, MGMT, DCC, RASSF1A, and AIM1). In Chinese population, the results of the study performed by Zhang et al. [115] showed that nine genes (APC, CDH13, KLK10, DLEC1, RASSF1A, EFEMP1, SFRP1, RARβ and p16(INK4A)) had a significantly higher frequency of methylation in NSCLC as compared with normal tissues, while several others (RUNX3, hMLH1, DAPK, BRCA1, p14(ARF), MGMT, NORE1A, FHIT, CMTM3, LSAMP and OPCML) showed relatively low sensitivity or specificity. Moreover, the nine genes validated in tumor tissues also showed a significantly higher frequency of tumor-specific hypermethylation in NSCLC plasma, as compared with cancer-free plasma, and a 5-gene set (APC, RASSF1A, CDH13, KLK10 and DLEC1) achieved a sensitivity of 83.64 % and a specificity of 74.0 % for cancer diagnosis.

As far as individual genes are concerned, there are many studies which provide new information on gene-specific hypermethylation. It has been proved that hypermethylation of particular genes correlates differently with tumor’s type, stage and smoking history. However, the methylation frequencies of the genes examined in NSCLC samples vary according to different study results. For example, in the study performed by Yanagawa et al. [116] the methylation frequency was 26 % for DAPK, 34 % for FHIT, 26 % for H-cadherin, 14 % for MGMT, 8 % for p14, 27 % for p16, 38 % for RAR-beta, 42 % for RASSF1A, 25 % for RUNX3, and 12 % for TIMP-3. Hypermethylation of RASSF1 and DAPK1 was found to be 100 % specific and together identified 39 % of NSCLC tissues. The results performed by Feng et al. [117] revealed high levels of methylation of six genes (RASSF1, DAPK1, BVES, CDH13, MGMT, or KCNH5) that were 100 % specific and identified 53 % of cancerous tissues. Additionally, some other loci showing significant differences in DNA methylation levels between tumor and non-tumor lung tissue have been identified, including: CDKN2A EX2, CDX2, HOXA1, SFPR1, and TWIST1 gene [118]. In another study, it has been documented that in analyzed panel of genes (3-OST-2, RASSF1A, DcR1, DcR2, P16, DAPK, APC, ECAD, HCAD, SOCS1, SOCS3) only 3-OST-2 followed by RASSF1A showed the highest level of promoter methylation in tumors as compared to controls. Moreover, 3-OST-2 promoter hypermethylation was associated with advanced tumor stage [119]. According to the numerous studies, the most frequently hypermethylated genes in NSCLC are listed in Table 4. Special attention is drawn to the role of gene hypermethylation in histopathological type differentiation, tumor stage, disease outcome and prognosis.

Besides the genes listed in Table 4, the results of studies assign several other hypermethylated genes to the particular histological types of NSCLC. For instance, CDKN2A, CDX2, HOXA1 and OPCML are more frequently silenced via hypermethylation in AC [118], while hypermethylated CALCA, EVX2, GDNF, MTHFR, OPCML, TNFRSF25, TCF21, PAX8, PTPRN2, PITX2, reveal correlation with SSC [120, 121].

Additionally, association between gene methylation and patient smoking history has been observed in many studies. Although, some results are opposite. While CDKN2A, DAPK1 and APC are found hypermethylated both in smoking and non-smoking lung cancer patients [122–125] others, like APC, FHIT, RASSF1A or CCND2 are strictly correlated with smoking [117, 123, 126–128].

The list of aberrantly methylated genes in lung cancer still expands. In future it might be useful in a more exact prognosis of lung cancer development at early stages of the disease.

Histone modifications in lung carcinogenesis

Dynamic histone modifications—in cooperation with the above discussed gene promoter methylation—play critical role in the modulation of chromatin conformation and the regulation of gene expression.

In cancer cells, including lung cancer, hypermethylation of promoter CpG islands of thus transcriptionally repressed tumor suppressor genes is associated with a particular combination of histone marks, such as deacetylation of histones H3 and H4, loss of histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4) trimethylation, and gain of H3K9 and H3K27 trimethylation [1, 8, 15]. Histone H2 and H3 acetylation and trimethylation status in NSCLC and SCLC allows the detection of subpopulations with differential prognosis. This suggests that epigenetic changes associated with histone code play important role in lung cancer tumorigenesis. Excessive acetylation of H4K5/H4K8 and loss of trimethylation of H4K20 was found in NSCLC and pre-invasive bronchial dysplastic lesions. The prognostic value of epigenetic changes involving multiple histones, in particular H2A (H2AK5ac) and H3 (H3K4me2, H3K9ac), is greater in early NSCLC, and the evaluation of these changes may help in selecting early-stage NSCLC patients for adjuvant treatment [129].

The further studies revealed that H4K20 loss of trimethylation identified a subpopulation of early stage (I) lung adenocarcinoma with shorter survival time [130]. Similarly, cellular levels of H3K4me2 and H3K18ac were lower and the observed histone modification patterns were independent predictors of clinical outcome in AC [131]. These results strongly indicated that the lower cellular levels of histone modifications were associated with decreased survival time. Interestingly, the levels of histone modifications correlated positively with each other: loss of one histone modification was generally associated with loss of other modifications within a patient [131].

Additionally, DNA repetitive elements—that are demethylated in cancer DNA—may also get demethylated and/or deacetylated on their associated histones. The biological effects of these alterations of histones at repetitive elements are unclear but the researchers suggest that they probably are associated with a more aggressive phenotype [131]. Generally, increased frequency of cancer cells with lower global levels of histone modifications indicates poorer clinical outcome, i.e., increased risk of tumor recurrence and/or decreased survival time. It has been demonstrated for several cancers, including lung cancer [69].

The mechanisms affecting histone modifications are still being discovered, and could be attributed to improper targeting, altered expression and/or activity of histone-modifying enzymes because of genetic mutations, expression changes, and/or posttranslational control [132]. The aberrant transcription of genes that encode histone acetyltransferase (HAT) or histone deacetylase (HDAC) enzymes or their binding partners, has been clearly linked to carcinogenesis [133]. The study results revealed that stronger HDAC1 expression in tumor cells was an independent predictor of a poor prognosis in patients with adenocarcinoma of the lung [134]. Thus, histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACis) are now attracting attention as promising therapeutic agents for the treatment of cancer. The effects of HDAC inhibitors on gene expression are highly selective, leading to transcriptional activation of certain genes such as cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21WAF1/CIP1 and repression of others. HDAC inhibition not only results in acetylation of histones but also transcription factors, such as p53, GATA-1 and estrogen receptor-alpha [135]. The results of numerous studies indicate that inhibition of HDACs by HDACis leads to transcriptional activation of genes involved in cancer cell growth, apoptosis, differentiation, migration and invasion. As demonstrated in several studies, induced acetylation of histones H3 and H4 by TSA in lung cancer cells led to re-expression of a number of TSGs, including TGFBR2, SATB1, C/EBPalpha, MYO18B, DAPK [67, 136–140]. The comprehensive study performed by Zhong et al. [141], involving high-throughput gene expression microarrays combined with pharmacologic inhibition of DNA methylation and histone deacetylation in NSCLC, uncovered over 200 genes upregulated by 5-azadC and TSA treatment. Some of those genes were induced by TSA alone (NRIP3, CYLD, CD9, ATF3, OXTR), confirming the role of histone deacetylation in their silencing. Table 5 summarizes the examples of genes and sequences targeted by histone modifications in lung cancer.

Epigenetic regulation of microRNA in lung carcinogenesis

So far, deregulation of miRNA expression has been demonstrated in lung cancer and its diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic significance has been underlined. The number of aberrantly expressed miRNAs is still growing. Additionally, it has been observed that global decrease of miRNA expression causally contributes to the transformed phenotype during lung tumorigenesis [142].

As mentioned earlier, besides genetic mechanisms disturbing miRNA expression, also epigenetic events can modulate the expression and regulatory role of miRNA. Aberrant regulation at this level was confirmed also in lung cancer. For instance, the expression of miRNA-124a was found to be epigenetically silenced by DNA hypermethylation and, as the study results have shown, DNA methyltransferase inhibitor (DNMTi) restored its expression [29]. Conversely, micro RNA let-7a-3 is upregulated in lung adenocarcinoma via hypomethylation. Its expression is associated with enhanced tumor phenotypes and oncogenic changes in transcription profiles [81].

Expression of miR-34 family—involved in lung carcinogenesis through p53 pathway—has also been reported to be regulated by DNA methylation. The results of recent analysis have revealed that promoter hypermethylation of miR-34b/c was correlated with a high probability of recurrence and associated with poor overall survival and disease-free survival in stage I NSCLC [143]. This was a relatively common event in NSCLC and might be regarded as a potential prognostic factor for stage I NSCLC.

Regarding another micro RNA with pro-apoptotic function and strongly downregulated in lung cancer, namely miR-212, Incoronato et al. [144] have found that its transcriptional inactivation in lung cancer is not associated to DNA hypermethylation status but to a change in the methylation status of histone tails linked to the promoter region of this microRNA. As the study results have shown, transcriptional silencing of miR-212 in NSCLC involved H3K27me3/H3K9Ac or H3K9me3/H3K9Ac-associated histone modification. Additionally, miR-212 downregulation was tightly associated with the severity of the disease, being significantly suppressed in T3/T4 staging rather than in T1/T2 staging [144].

Another mechanism underlying the regulatory role of micro-RNA and associated with epigenetic modifications has been discovered in case of microRNA-449. This miRNA belongs to the group of so called epi-miRNAs, interacting with the members of epigenetic machinery. The study results indicate that downexpression of miR-449a/b might be one of mechanisms responsible for over-expression of HDAC1 in lung cancer. MicroRNA-449a/b, possessing tumor suppressor function, inhibits cell growth and anchorage-independent growth. It has been shown, that co-treatment with miR-449a and HDAC inhibitors leads to significant tumor growth reduction as compared with HDAC inhibitor mono-treatment. These results suggest that miR-449a/b might be a potential therapeutic candidate in patients with primary lung cancer [145]. Another epi-miRNAs belong to miR-29 family (29a, 29b, and 29c), which target the de novo DNA methyltransferases DNMT-3A and 3B. In lung cancer miR-29s expression has been found to be inversely correlated with both enzymes [146]. According to the study results, the enforced expression of miR-29s in lung cancer cell lines results in a global reduction of DNA methylation, thus leading to re-expression of methylation-silenced tumor suppressor genes (FHIT, WWOX) and, additionally, inhibits tumorigenicity in vitro and in vivo.

The study findings support a role of epi-miRNAs in epigenetic normalization of NSCLC. They could be a basis for the development of miRNA-based strategies for the treatment of lung cancer (Table 5).

The findings on miRNA regulation via epigenetic mechanisms in lung cancer are listed in Table 6.

Conclusions

In the past decade epigenetics has been one of the most promising and rapidly expanding research fields. Since the discovery of altered DNA methylation patterns, i.e., global DNA hypomethylation and tumor suppressor promoter hypermethylation in cancer cells, in 1980s–1990s, a variety of other epigenetic changes have been identified. They include a wide spectrum of histone modifications and the role of non-coding RNAs. Nowadays a huge amount of knowledge confirms that the epigenetic setting is completely disturbed in human cancer. Epigenetic processes play a key role in the onset and progression of numerous types of tumors.

In lung cancer promoter DNA hypermethylation, identified for still growing number of TSGs, and single gene hypomethylation, are recognized as belonging to the earliest events in lung carcinogenesis and increasing with the disease progression. Cancer-specific hypermethylation and hypomethylation events can be recognized in lung tissue biopsies, but also in biological fluids, like sputum, allowing to predict lung cancer incidence using non-invasive methods. Specific epigenetic biomarkers, associated with hyper- or hypomethylation, can distinguish NSCLC subtypes or reveal early stages of lung tumorigenesis affecting smokers. Aberrant methylation of certain genes is associated with poor outcome and can be useful for the establishment of lung tumor prognosis.

In the recent years, histone-based and miRNA-based epigenetic signatures have also been incorporated into the molecular search for biomarkers in cancer. Specific histone code can support the selection of early stage disease patients and predict their clinical outcome. Additionally, the role of miRNAs, the very recently discovered level of epigenetic control, is gaining importance. The aberrant expression of several miRNAs has been associated with differential diagnosis of NSCLC as well as with survival and cancer recurrence in lung cancer patients.

As potentially reversible, epigenetic aberrations are the targets for potential treatment strategies in cancer therapy. The growing number of reports outline the usefulness of the epigenetic events for lung cancer diagnostic, prognostic and targeted epigenetic therapy.

References

Jones PA, Baylin SB (2007) The epigenomics of cancer. Cell 128:683–692

Feinberg AP, Ohlsson R, Henikoff S (2006) The epigenetic progenitor origin of human cancer. Nat Rev Genet 7:21–33

Chan TA, Glockner S, Yi JM, Chen W, Van Neste L, Cope L, Herman JG, Velculescu V, Schuebel KE, Ahuja N, Baylin SB (2008) Convergence of mutation and epigenetic alterations identifies common genes in cancer that predict for poor prognosis. PLoS Med 5:e114

Herman JG, Baylin SB (2003) Gene silencing in cancer in association with promoter hypermethylation. N Engl J Med 349:2042–2054

Feinberg AP (2001) Cancer epigenetics takes center stage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:392–394

Brena RM, Costello JF (2007) Genome-epigenome interactions in cancer. Hum Mol Genet 16:R96–R105

Jacinto FV, Esteller M (2007) Mutator pathways unleashed by epigenetic silencing in human cancer. Mutagenesis 22:247–253

Sharma S, Kelly TK, Jones PA (2010) Epigenetics in cancer. Carcinogenesis 31:27–36

Holliday R (2006) Epigenetics: a historical overview. Epigenetics 1:76–80

Robertson KD (2005) DNA methylation and human disease. Nat Rev Genet 6:597–610

Vaissière T, Sawan C, Herceg Z (2008) Epigenetic interplay between histone modifications and DNA methylation in gene silencing. Mutat Res 659:40–48

Robertson KD (2002) DNA methylation and chromatin—unraveling the tangled web. Oncogene 21:5361–5379

Hendrickson DG, Hogan DJ, McCullough HL, Myers JW, Herschlag D, Ferrell JE, Brown PO (2009) Concordant regulation of translation and mRNA abundance for hundreds of targets of a human microRNA. PLoS Biol 7:e1000238

Xing M (2008) Recent advances in molecular biology of thyroid cancer and their clinical implications. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 41:1135–1146

Kondo Y (2009) Epigenetic cross-talk between DNA methylation and histone modifications in human cancers. Yonsei Med J 50:455–463

Jenuwein T, Allis CD (2001) Translating the histone code. Science 293:1074–1080

Kouzarides T (2007) Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell 128:693–705

Cheung P, Lau P (2005) Epigenetic regulation by histone methylation and histone variants. Mol Endocrinol 19:563–573

Kouzarides T (2002) Histone methylation in transcriptional control. Curr Opin Genet Dev 12:198–209

Berger SL (2007) The complex language of chromatin regulation during transcription. Nature 447:407–412

Kim GD, Ni J, Kelesoglu N, Roberts RJ, Pradhan S (2002) Co-operation and communication between the human maintenance and de novo DNA (cytosine-5) methyltransferases. EMBO J 21:4183–4195

Bestor TH (2000) The DNA methyltransferases of mammals. Hum Mol Genet 9:2395–2402

Kanai Y, Hirohashi S (2007) Alterations of DNA methylation associated with abnormalities of DNA methyltransferases in human cancers during transition from a precancerous to a malignant state. Carcinogenesis 28:2434–2442

Bird A (2002) DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev 16:6–21

Mossman D, Kim KT, Scott RJ (2010) Demethylation by 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine in colorectal cancer cells targets genomic DNA whilst promoter CpG island methylation persists. BMC Cancer 10:366

Palii SS, Robertson KD (2007) Epigenetic control of tumor suppression. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr 17:295–316

Xing M (2007) Gene methylation in thyroid tumorigenesis. Endocrinology 148(3):948–953

D’Alessio AC, Szyf M (2006) Epigenetic tête-à-tête: the bilateral relationship between chromatin modifications and DNA methylation. Biochem Cell Biol 84:463–476

Lujambio A, Ropero S, Ballestar E, Fraga MF, Cerrato C, Setién F, Casado S, Suarez-Gauthier A, Sanchez-Cespedes M, Git A, Spiteri I, Das PP, Caldas C, Miska E, Esteller M (2007) Genetic unmasking of an epigenetically silenced microRNA in human cancer cells. Cancer Res 67:1424–1429

Weber B, Stresemann C, Brueckner B, Lyko F (2007) Methylation of human microRNA genes in normal and neoplastic cells. Cell Cycle 6:1001–1005

Lehmann U, Hasemeier B, Christgen M, Müller M, Römermann D, Länger F, Kreipe H (2008) Epigenetic inactivation of microRNA gene hsa-mir-9-1 in human breast cancer. J Pathol 214:17–24

Scott GK, Mattie MD, Berger CE, Benz SC, Benz CC (2006) Rapid alteration of microRNA levels by histone deacetylase inhibition. Cancer Res 66:1277–1281

Jones PA (1996) DNA methylation errors and cancer. Cancer Res 56:2463–2467

Byun DS, Lee MG, Chae KS, Ryu BG, Chi SG (2001) Frequent epigenetic inactivation of RASSF1A by aberrant promoter hypermethylation in human gastric adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 61:7034–7038

Ehrlich M (2002) DNA methylation in cancer: too much, but also too little. Oncogene 21:5400–5413

Costello JF, Frühwald MC, Smiraglia DJ et al (2000) Aberrant CpG-island methylation has non-random and tumour-type-specific patterns. Nat Genet 24:132–138

Ehrlich M (2009) DNA hypomethylation in cancer cells. Epigenomics 1:239–259

Dunn BK (2003) Hypomethylation: one side of a larger picture. Ann NY Acad Sci 983:28–42

Esteller M (2008) Epigenetics in cancer. N Engl J Med 358:1148–1159

Kanai Y (2010) Genome-wide DNA methylation profiles in precancerous conditions and cancers. Cancer Sci 101:36–45

Jarmalaite S, Jankevicius F, Kurgonaite K, Suziedelis K, Mutanen P, Husgafvel-Pursiainen K (2008) Promoter hypermethylation in tumour suppressor genes shows association with stage, grade and invasiveness of bladder cancer. Oncology 75:145–151

Park SY, Kim BH, Kim JH, Cho NY, Choi M, Yu EJ, Lee S, Kang GH (2007) Methylation profiles of CpG island loci in major types of human cancers. J Korean Med Sci 22:311–317

Costa VL, Henrique R, Ribeiro FR, Pinto M, Oliveira J, Lobo F, Teixeira MR, Jerónimo C (2007) Quantitative promoter methylation analysis of multiple cancer-related genes in renal cell tumors. BMC Cancer 7:133

Shames DS, Girard L, Gao B, Sato M, Lewis CM, Shivapurkar N, Jiang A, Perou CM, Kim YH, Pollack JR, Fong KM, Lam CL, Wong M, Shyr Y, Nanda R, Olopade OI, Gerald W, Euhus DM, Shay JW, Gazdar AF, Minna JD (2006) A genome-wide screen for promoter methylation in lung cancer identifies novel methylation markers for multiple malignancies. PLoS Med 3:e486

Singal R, Ferdinand L, Reis IM, Schlesselman JJ (2004) Methylation of multiple genes in prostate cancer and the relationship with clinicopathological features of disease. Oncol Rep 12:631–637

Wong IH, Chan J, Wong J, Tam PK (2004) Ubiquitous aberrant RASSF1A promoter methylation in childhood neoplasia. Clin Cancer Res 10:994–1002

Psofaki V, Kalogera C, Tzambouras N, Stephanou D, Tsianos E, Seferiadis K, Kolios G (2010) Promoter methylation status of hMLH1, MGMT, and CDKN2A/p16 in colorectal adenomas. World J Gastroenterol 16:3553–3560

Arai E, Ushijima S, Fujimoto H, Hosoda F, Shibata T, Kondo T, Yokoi S, Imoto I, Inazawa J, Hirohashi S, Kanai Y (2009) Genome-wide DNA methylation profiles in both precancerous conditions and clear cell renal cell carcinomas are correlated with malignant potential and patient outcome. Carcinogenesis 30:214–221

Arai E, Ushijima S, Gotoh M, Ojima H, Kosuge T, Hosoda F, Shibata T, Kondo T, Yokoi S, Imoto I, Inazawa J, Hirohashi S, Kanai Y (2009) Genome-wide DNA methylation profiles in liver tissue at the precancerous stage and in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer 125:2854–2862

Ahlquist T, Lind GE, Costa VL, Meling GI, Vatn M, Hoff GS, Rognum TO, Skotheim RI, Thiis-Evensen E, Lothe RA (2008) Gene methylation profiles of normal mucosa, and benign and malignant colorectal tumors identify early onset markers. Mol Cancer 7:94

Euhus DM, Bu D, Milchgrub S, Xie XJ, Bian A, Leitch AM, Lewis CM (2008) DNA methylation in benign breast epithelium in relation to age and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17:1051–1059

Qian ZR, Sano T, Yoshimoto K, Asa SL, Yamada S, Mizusawa N, Kudo E (2007) Tumor-specific downregulation and methylation of the CDH13 (H-cadherin) and CDH1 (E-cadherin) genes correlate with aggressiveness of human pituitary adenomas. Mod Pathol 20:1269–1277

Arai E, Kanai Y, Ushijima S, Fujimoto H, Mukai K, Hirohashi S (2006) Regional DNA hypermethylation and DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) 1 protein overexpression in both renal tumors and corresponding nontumorous renal tissues. Int J Cancer 119:288–296

Hoque MO, Rosenbaum E, Westra WH, Xing M, Ladenson P, Zeiger MA, Sidransky D, Umbricht CB (2005) Quantitative assessment of promoter methylation profiles in thyroid neoplasms. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:4011–4018

Chan AO, Broaddus RR, Houlihan PS, Issa JP, Hamilton SR, Rashid A (2002) CpG island methylation in aberrant crypt foci of the colorectum. Am J Pathol 160:1823–1830

Nass SJ, Herman JG, Gabrielson E, Iversen PW, Parl FF, Davidson NE, Graff JR (2000) Aberrant methylation of the estrogen receptor and E-cadherin 5′ CpG islands increases with malignant progression in human breast cancer. Cancer Res 60:4346–4348

Toyota M, Ahuja N, Ohe-Toyota M, Herman JG, Baylin SB, Issa JP (1999) CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:8681–8686

Jing F, Yuping W, Yong C, Jie L, Jun L, Xuanbing T, Lihua H (2010) CpG island methylator phenotype of multigene in serum of sporadic breast carcinoma. Tumour Biol 31:321–331

Liu Z, Li W, Lei Z, Zhao J, Chen XF, Liu R, Peng X, Wu ZH, Chen J, Liu H, Zhou QH, Zhang HT (2010) CpG island methylator phenotype involving chromosome 3p confers an increased risk of non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 5:790–797

Park SY, Kook MC, Kim YW, Cho NY, Jung N, Kwon HJ, Kim TY, Kang GH (2010) CpG island hypermethylator phenotype in gastric carcinoma and its clinicopathological features. Virchows Arch 457:415–422

Yang XJ, Seto E (2007) HATs and HDACs: from structure, function and regulation to novel strategies for therapy and prevention. Oncogene 26:5310–5318

Kim GW, Yang XJ (2011) Comprehensive lysine acetylomes emerging from bacteria to humans. Trends Biochem Sci 36:211–220

Cedar H, Bergman Y (2009) Linking DNA methylation and histone modification: patterns and paradigms. Nat Rev Genet 10:295–304

Glozak MA, Seto E (2007) Histone deacetylases and cancer. Oncogene 26:5420–5432

Yasui W, Oue N, Ono S, Mitani Y, Ito R, Nakayama H (2003) Histone acetylation and gastrointestinal carcinogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 983:220–231

Valk-Lingbeek ME, Bruggeman SW, Van Lohuizen M (2004) Stem cells and cancer; the polycomb connection. Cell 118:409–418

Selinger CI, Cooper WA, Al-Sohaily S, Mladenova DN, Pangon L, Kennedy CW, McCaughan BC, Stirzaker C, Kohonen-Corish MR (2011) Loss of special AT-rich binding protein 1 expression is a marker of poor survival in lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 6:1179–1189

Cadieux B, Ching TT, Vandenberg SR, Costello JF (2006) Genome-wide hypomethylation in human glioblastomas associated with specific copy number alteration, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase allele status, and increased proliferation. Cancer Res 66:8469–8476

Kurdistani SK (2011) Histone modifications in cancer biology and prognosis. Prog Drug Res 67:91–106

Vasudevan S, Tong Y, Steitz JA (2007) Switching from repression to activation: microRNAs can up-regulate translation. Science 318:1931–1934

Calin GA, Croce CM (2006) MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer 6:857–866

Motoyama K, Inoue H, Takatsuno Y, Tanaka F, Mimori K, Uetake H, Sugihara K, Mori M (2009) Over- and under-expressed microRNAs in human colorectal cancer. Int J Oncol 34:1069–1075

Takamizawa J, Konishi H, Yanagisawa K, Tomida S, Osada H, Endoh H, Harano T, Yatabe Y, Nagino M, Nimura Y, Mitsudomi T, Takahashi T (2004) Reduced expression of the let-7 microRNAs in human lung cancers in association with shortened postoperative survival. Cancer Res 64:3753–3756

Calin GA, Sevignani C, Dumitru CD, Hyslop T, Noch E, Yendamuri S, Shimizu M, Rattan S, Bullrich F, Negrini M, Croce CM (2004) Human microRNA genes are frequently located at fragile sites and genomic regions involved in cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:2999–3004

Melo SA, Esteller M (2011) A precursor microRNA in a cancer cell nucleus: get me out of here! Cell Cycle 10:922–925

Bueno MJ, Pérez de Castro I, Gómez de Cedrón M, Santos J, Calin GA, Cigudosa JC, Croce CM, Fernández-Piqueras J, Malumbres M (2008) Genetic and epigenetic silencing of microRNA-203 enhances ABL1 and BCR-ABL1 oncogene expression. Cancer Cell 13:496–506

Toyota M, Suzuki H, Sasaki Y, Maruyama R, Imai K, Shinomura Y, Tokino T (2008) Epigenetic silencing of microRNA-34b/c and B-cell translocation gene 4 is associated with CpG island methylation in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 68:4123–4132

Kozaki K, Imoto I, Mogi S, Omura K, Inazawa J (2008) Exploration of tumor-suppressive microRNAs silenced by DNA hypermethylation in oral cancer. Cancer Res 68(7):2094–2105

Saito Y, Friedman JM, Chihara Y, Egger G, Chuang JC, Liang G (2009) Epigenetic therapy upregulates the tumor suppressor microRNA-126 and its host gene EGFL7 in human cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 379:726–731

Furuta M, Kozaki KI, Tanaka S, Arii S, Imoto I, Inazawa J (2010) MiR-124 and miR-203 are epigenetically silenced tumor-suppressive microRNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis 31(5):766–776

Brueckner B, Stresemann C, Kuner R, Mund C, Musch T, Meister M, Sültmann H, Lyko F (2007) The human let-7a-3 locus contains an epigenetically regulated microRNA gene with oncogenic function. Cancer Res 67:1419–1423

Saito Y, Liang G, Egger G, Friedman JM, Chuang JC, Coetzee GA, Jones PA (2006) Specific activation of microRNA-127 with downregulation of the proto-oncogene BCL6 by chromatin-modifying drugs in human cancer cells. Cancer Cell 9:435–443

Bandres E, Agirre X, Bitarte N, Ramirez N, Zarate R, Roman-Gomez J, Prosper F, Garcia-Foncillas J (2009) Epigenetic regulation of microRNA expression in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer 125:2737–2743

Melo SA, Esteller M (2011) Dysregulation of microRNAs in cancer: playing with fire. FEBS Lett 585:2087–2099

Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A (2012) Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 62:10–29

Travis WD, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC (2004) Pathology and genetics. WHO Classification of tumours: tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart, chap 1. IARC Press, Lyon

Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M et al (2011) International association for the study of lung cancer/american thoracic society/european respiratory society international multidisciplinary-classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol 6:244–285

Feinberg AP, Vogelstein B (1983) Hypomethylation distinguishes genes of some human cancers from their normal counterparts. Nature 301:89–92

Wilson AS, Power BE, Molloy PL (2007) DNA hypomethylation and human diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta 1775:138–162

Ogino S, Nosho K, Kirkner GJ, Kawasaki T, Chan AT, Schernhammer ES, Giovannucci EL, Fuchs CS (2008) A cohort study of tumoral LINE-1 hypomethylation and prognosis in colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 100:1734–1738

Pattamadilok J, Huapai N, Rattanatanyong P, Vasurattana A, Triratanachat S, Tresukosol D, Mutirangura A (2008) LINE-1 hypomethylation level as a potential prognostic factor for epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 18:711–717

Roman-Gomez J, Jimenez-Velasco A, Agirre X, Cervantes F, Sanchez J, Garate L, Barrios M, Castillejo JA, Navarro G, Colomer D, Prosper F, Heiniger A, Torres A (2005) Promoter hypomethylation of the LINE-1 retrotransposable elements activates sense/antisense transcription and marks the progression of chronic myeloid leukemia. Oncogene 24:7213–7223

Pavicic W, Joensuu EI, Nieminen T, Peltomäki P (2012) LINE-1 hypomethylation in familial and sporadic cancer. J Mol Med (Berl) [Epub ahead of print]

Piskareva O, Lackington W, Lemass D, Hendrick C, Doolan P, Barron N (2011) The human L1 element: a potential biomarker in cancer prognosis, current status and future directions. The human L1 element: a potential biomarker in cancer prognosis, current status and future directions. Curr Mol Med 11:286–303

Kazazian HH Jr, Goodier JL (2002) LINE drive. retrotransposition and genome instability. Cell 110:277–280

Symer DE, Connelly C, Szak ST, Caputo EM, Cost GJ, Parmigiani G, Boeke JD (2002) Human L1 retrotransposition is associated with genetic instability in vivo. Cell 110:327–338

Choma D, Daures JP, Quantin X, Pujol JL (2001) Aneuploidy and prognosis of non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis of published data. Br J Cancer 85:14–22

Saito K, Kawakami K, Matsumoto I, Oda M, Watanabe G, Minamoto T (2010) Long interspersed nuclear element 1 hypomethylation is a marker of poor prognosis in stage IA non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 16:2418–2426

Daskalos A, Logotheti S, Markopoulou S, Xinarianos G, Gosney JR, Kastania AN, Zoumpourlis V, Field JK, Liloglou T (2011) Global DNA hypomethylation-induced ΔNp73 transcriptional activation in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Lett 300:79–86

Glazer CA, Smith IM, Ochs MF, Begum S, Westra W, Chang SS, Sun W, Bhan S, Khan Z, Ahrendt S, Califano JA (2009) Integrative discovery of epigenetically derepressed cancer testis antigens in NSCLC. PLoS ONE 4:e8189

Kayser G, Sienel W, Kubitz B, Mattern D, Stickeler E, Passlick B, Werner M, Zur Hausen A (2011) Poor outcome in primary non-small cell lung cancers is predicted by transketolase TKTL1 expression. Pathology 43:719–724

Klenova EM, Morse HC 3rd, Ohlsson R, Lobanenkov VV (2002) The novel BORIS + CTCF gene family is uniquely involved in the epigenetics of normal biology and cancer. Semin Cancer Biol 12:399–414

Pugacheva EM, Suzuki T, Pack SD, Kosaka-Suzuki N, Yoon J, Vostrov AA, Barsov E, Strunnikov AV, Morse HC 3rd, Loukinov D, Lobanenkov V (2010) The structural complexity of the human BORIS gene in gametogenesis and cancer. PLoS ONE 5:e13872

Martin-Kleiner I (2011) BORIS in human cancers—a review. Eur J Cancer [Epub ahead of print]

Renaud S, Pugacheva EM, Delgado DM, Braunschweig R, Abdullaev Z, Loukinov D, Benhattar J, Lobanenkov V (2007) Expression of the CTCF-paralogous cancer-testis gene, brother of the regulator of imprinted sites (BORIS), is regulated by three alternative promoters modulated by CpG methylation and by CTCF and p53 transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Res 35:7372–7388

Bhan S, Negi SS, Shao C, Glazer CA, Chuang A, Gaykalova DA, Sun W, Sidransky D, Ha PK, Califano JA (2011) BORIS binding to the promoters of cancer testis antigens, MAGEA2, MAGEA3, and MAGEA4, is associated with their transcriptional activation in lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 17:4267–4276

Fiorentino FP, Macaluso M, Miranda F et al (2011) CTCF and BORIS regulate Rb2/p130 gene transcription: a novel mechanism and a new paradigm for understanding the biology of lung cancer. Mol Cancer Res 9:225–233

Radhakrishnan VM, Jensen TJ, Cui H, Futscher BW, Martinez JD (2011) Hypomethylation of the 14–3-3? promoter leads to increased expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 50:830–836

Stewart DJ (2010) Tumor and host factors that may limit efficacy of chemotherapy in non-small cell and small cell lung cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 75:173–234

Gu Y, Wang C, Wang Y, Qiu X, Wang E (2009) Expression of thymosin beta10 and its role in non-small cell lung cancer. Hum Pathol 40:117–124

Chen WY, Zeng X, Carter MG, Morrell CN, Chiu Yen RW, Esteller M, Watkins DN, Herman JG, Mankowski JL, Baylin SB (2003) Heterozygous disruption of Hic1 predisposes mice to a gender-dependent spectrum of malignant tumors. Nat Genet 33:197–202

Kwon YJ, Lee SJ, Koh JS, Kim SH, Lee HW, Kang MC, Bae JB, Kim YJ, Park JH (2011) Genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation and the gene expression change in lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol [Epub ahead of print]

Cortese R, Hartmann O, Berlin K, Eckhardt F (2008) Correlative gene expression and DNA methylation profiling in lung development nominate new biomarkers in lung cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 40:1494–1508

Begum S, Brait M, Dasgupta S, Ostrow KL, Zahurak M, Carvalho AL, Califano JA, Goodman SN, Westra WH, Hoque MO, Sidransky D (2011) An epigenetic marker panel for detection of lung cancer using cell-free serum DNA. Clin Cancer Res 17:4494–4503

Zhang Y, Wang R, Song H, Huang G, Yi J, Zheng Y, Wang J, Chen L (2011) Methylation of multiple genes as a candidate biomarker in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Lett 303:21–28

Yanagawa N, Tamura G, Oizumi H, Kanauchi N, Endoh M, Sadahiro M, Motoyama T (2007) Promoter hypermethylation of RASSF1A and RUNX3 genes as an independent prognostic prediction marker in surgically resected non-small cell lung cancers. Lung Cancer 58:131–138

Feng Q, Hawes SE, Stern JE, Wiens L, Lu H, Dong ZM, Jordan CD, Kiviat NB, Vesselle H (2008) DNA methylation in tumor and matched normal tissues from non-small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17:645–654

Tsou JA, Galler JS, Siegmund KD, Laird PW, Turla S, Cozen W, Hagen JA, Koss MN, Laird-Offringa IA (2007) Identification of a panel of sensitive and specific DNA methylation markers for lung adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer 6:70

Shivapurkar N, Stastny V, Suzuki M, Wistuba II, Li L, Zheng Y, Feng Z, Hol B, Prinsen C, Thunnissen FB, Gazdar AF (2007) Application of a methylation gene panel by quantitative PCR for lung cancers. Cancer Lett 247:56–71

Ji M, Guan H, Gao C, Shi B, Hou P (2011) Highly frequent promoter methylation and PIK3CA amplification in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). BMC Cancer 11:147

Anglim PP, Galler JS, Koss MN, Hagen JA, Turla S, Campan M, Weisenberger DJ, Laird PW, Siegmund KD, Laird-Offringa IA (2008) Identification of a panel of sensitive and specific DNA methylation markers for squamous cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer 7:62

Brabender J, Usadel H, Danenberg KD, Metzger R, Schneider PM, Lord RV, Wickramasinghe K, Lum CE, Park J, Salonga D, Singer J, Sidransky D, Hölscher AH, Meltzer SJ, Danenberg PV (2001) Adenomatous polyposis coli gene promoter hypermethylation in non-small cell lung cancer is associated with survival. Oncogene 20:3528–3532

Kim DH, Nelson HH, Wiencke JK, Zheng S, Christiani DC, Wain JC, Mark EJ, Kelsey KT (2001) p16(INK4a) and histology-specific methylation of CpG islands by exposure to tobacco smoke in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res 61:3419–3424

Kim DH, Nelson HH, Wiencke JK, Christiani DC, Wain JC, Mark EJ, Kelsey KT (2001) Promoter methylation of DAP-kinase: association with advanced stage in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene 20:1765–1770

Sanchez-Cespedes M, Ahrendt SA, Piantadosi S, Rosell R, Monzo M, Wu L, Westra WH, Yang SC, Jen J, Sidransky D (2001) Chromosomal alterations in lung adenocarcinoma from smokers and nonsmokers. Cancer Res 61:1309–1313

Toyooka S, Maruyama R, Toyooka KO, McLerran D, Feng Z, Fukuyama Y, Virmani AK, Zochbauer-Muller S, Tsukuda K, Sugio K, Shimizu N, Shimizu K, Lee H, Chen CY, Fong KM, Gilcrease M, Roth JA, Minna JD, Gazdar AF (2003) Smoke exposure, histologic type and geography-related differences in the methylation profiles of non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer 103:153–160

Verri C, Roz L, Conte D, Liloglou T, Livio A, Vesin A, Fabbri A, Andriani F, Brambilla C, Tavecchio L, Calarco G, Calabro E, Mancini A, Tosi D, Bossi P, Field JK, Brambilla E, Sozzi G (2009) EUELC Consortium. Fragile histidine triad gene inactivation in lung cancer: the European Early Lung Cancer project. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 179:396–401

Toyooka S, Suzuki M, Tsuda T, Toyooka KO, Maruyama R, Tsukuda K, Fukuyama Y, Iizasa T, Fujisawa T, Shimizu N, Minna JD, Gazdar AF (2004) Dose effect of smoking on aberrant methylation in non-small cell lung cancers. Int J Cancer 110:462–464

Barlési F, Giaccone G, Gallegos-Ruiz MI, Loundou A, Span SW, Lefesvre P, Kruyt FA, Rodriguez JA (2007) Global histone modifications predict prognosis of resected non small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 25:4358–4364

Van Den Broeck A, Brambilla E, Moro-Sibilot D, Lantuejoul S, Brambilla C, Eymin B, Khochbin S, Gazzeri S (2008) Loss of histone H4K20 trimethylation occurs in preneoplasia and influences prognosis of non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 14:7237–7245

Seligson DB, Horvath S, McBrian MA, Mah V, Yu H, Tze S, Wang Q, Chia D, Goodglick L, Kurdistani SK (2009) Global levels of histone modifications predict prognosis in different cancers. Am J Pathol 174:1619–1628

Esteller M (2006) Epigenetics provides a new generation of oncogenes and tumour-suppressor genes. Br J Cancer 94:179–183

Mai A, Massa S, Rotili D, Cerbara I, Valente S, Pezzi R, Simeoni S, Ragno R (2005) Histone deacetylation in epigenetics: an attractive target for anticancer therapy. Med Res Rev 25:261–309

Minamiya Y, Ono T, Saito H, Takahashi N, Ito M, Mitsui M, Motoyama S, Ogawa J (2011) Expression of histone deacetylase 1 correlates with a poor prognosis in patients with adenocarcinoma of the lung. Lung Cancer 74:300–304

Vigushin DM, Coombes RC (2002) Histone deacetylase inhibitors in cancer treatment. Anticancer Drugs 13:1–13

Halder SK, Cho YJ, Datta A, Anumanthan G, Ham AJ, Carbone DP, Datta PK (2011) Elucidating the mechanism of regulation of transforming growth factor ß Type II receptor expression in human lung cancer cell lines. Neoplasia 13:912–922

Osada H, Tatematsu Y, Sugito N, Horio Y, Takahashi T (2005) Histone modification in the TGFbetaRII gene promoter and its significance for responsiveness to HDAC inhibitor in lung cancer cell lines. Mol Carcinog 44:233–241

Tada Y, Brena RM, Hackanson B, Morrison C, Otterson GA, Plass C (2006) Epigenetic modulation of tumor suppressor CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha activity in lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 98:396–406

Tani M, Ito J, Nishioka M, Kohno T, Tachibana K, Shiraishi M, Takenoshita S, Yokota J (2004) Correlation between histone acetylation and expression of the MYO18B gene in human lung cancer cells. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 40:146–151

Toyooka S, Toyooka KO, Miyajima K, Reddy JL, Toyota M, Sathyanarayana UG, Padar A, Tockman MS, Lam S, Shivapurkar N, Gazdar AF (2003) Epigenetic down-regulation of death-associated protein kinase in lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res 9:3034–3041

Zhong S, Fields CR, Su N, Pan YX, Robertson KD (2007) Pharmacologic inhibition of epigenetic modifications, coupled with gene expression profiling, reveals novel targets of aberrant DNA methylation and histone deacetylation in lung cancer. Oncogene 26:2621–2634

Kumar MS, Lu J, Mercer KL, Golub TR, Jacks T (2007) Impaired microRNA processing enhances cellular transformation and tumorigenesis. Nat Genet 39:673–677

Wang Z, Chen Z, Gao Y, Li N, Li B, Tan F, Tan X, Lu N, Sun Y, Sun J, Sun N, He J (2011) DNA hypermethylation of microRNA-34b/c has prognostic value for stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Biol Ther 11:490–496

Incoronato M, Urso L, Portela A, Laukkanen MO, Soini Y, Quintavalle C, Keller S, Esteller M, Condorelli G (2011) Epigenetic regulation of miR-212 expression in lung cancer. PLoS ONE 6:e27722

Jeon HS, Lee SY, Lee EJ, Yun SC, Cha EJ, Choi E, Na MJ, Park JY, Kang J, Son JW (2011) Combining microRNA-449a/b with a HDAC inhibitor has a synergistic effect on growth arrest in lung cancer. Lung Cancer [Epub ahead of print]

Fabbri M, Garzon R, Cimmino A, Liu Z, Zanesi N, Callegari E, Liu S, Alder H, Costinean S, Fernandez-Cymering C, Volinia S, Guler G, Morrison CD, Chan KK, Marcucci G, Calin GA, Huebner K, Croce CM (2007) MicroRNA-29 family reverts aberrant methylation in lung cancer by targeting DNA methyltransferases 3A and 3B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:15805–15810

Chuang JC, Jones PA (2007) Epigenetics and microRNAs. Pediatr Res 61:24R–29R

Lujambio A, Calin GA, Villanueva A, Ropero S, Sánchez-Céspedes M, Blanco D, Montuenga LM, Rossi S, Nicoloso MS, Faller WJ, Gallagher WM, Eccles SA, Croce CM, Esteller M (2008) A microRNA DNA methylation signature for human cancer metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:13556–13561

Laneve P, Di Marcotullio L, Gioia U, Fiori ME, Ferretti E, Gulino A, Bozzoni I, Caffarelli E (2007) The interplay between microRNAs and the neurotrophin receptor tropomyosin-related kinase C controls proliferation of human neuroblastoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:7957–7962

Vogt M, Munding J, Grüner M, Liffers ST, Verdoodt B, Hauk J, Steinstraesser L, Tannapfel A, Hermeking H (2011) Frequent concomitant inactivation of miR-34a and miR-34b/c by CpG methylation in colorectal, pancreatic, mammary, ovarian, urothelial, and renal cell carcinomas and soft tissue sarcomas. Virchows Arch 458:313–322

Welch C, Chen Y, Stallings RL (2007) MicroRNA-34a functions as a potential tumor suppressor by inducing apoptosis in neuroblastoma cells. Oncogene 26:5017–5022

Agirre X, Vilas-Zornoza A, Jiménez-Velasco A, Martin-Subero JI, Cordeu L, Gárate L, San José-Eneriz E, Abizanda G, Rodríguez-Otero P, Fortes P, Rifón J, Bandrés E, Calasanz MJ, Martín V, Heiniger A, Torres A, Siebert R, Román-Gomez J, Prósper F (2009) Epigenetic silencing of the tumor suppressor microRNA Hsa-miR-124a regulates CDK6 expression and confers a poor prognosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Res 69:4443–4453

Fish JE, Santoro MM, Morton SU, Yu S, Yeh RF, Wythe JD, Ivey KN, Bruneau BG, Stainier DY, Srivastava D (2008) miR-126 regulates angiogenic signaling and vascular integrity. Dev Cell 15:272–284

Kozaki K, Imoto I, Mogi S, Omura K, Inazawa J (2008) Exploration of tumor-suppressive microRNAs silenced by DNA hypermethylation in oral cancer. Cancer Res 68:2094–2105

Park SM, Gaur AB, Lengyel E, Peter ME (2008) The miR-200 family determines the epithelial phenotype of cancer cells by targeting the E-cadherin repressors ZEB1 and ZEB2. Genes Dev 22:894–907

Saito Y, Suzuki H, Tsugawa H, Nakagawa I, Matsuzaki J, Kanai Y, Hibi T (2009) Chromatin remodeling at Alu repeats by epigenetic treatment activates silenced microRNA-512-5p with downregulation of Mcl-1 in human gastric cancer cells. Oncogene 28:2738–2744

Lu L, Katsaros D, Zhu Y, Hoffman A, Luca S, Marion CE, Mu L, Risch H, Yu H (2011) Let-7a regulation of insulin-like growth factors in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 126:687–694

Lu L, Katsaros D, de la Longrais IA, Sochirca O, Yu H (2007) Hypermethylation of let-7a-3 in epithelial ovarian cancer is associated with low insulin-like growth factor-II expression and favorable prognosis. Cancer Res 67:10117–10122

Kim SH, Lee S, Lee CH, Lee MK, Kim YD, Shin DH, Choi KU, Kim JY, Park do Y, Sol MY (2009) Expression of cancer-testis antigens MAGE-A3/6 and NY-ESO-1 in non-small-cell lung carcinomas and their relationship with immune cell infiltration. Lung 187:401–411

Lee SM, Lee WK, Kim DS, Park JY (2012) Quantitative promoter hypermethylation analysis of RASSF1A in lung cancer: comparison with methylation-specific PCR technique and clinical significance. Mol Med Rep 5:239–244

Suzuki M, Yoshino I (2010) Aberrant methylation in non-small cell lung cancer. Surg Today 40:602–607

Grote HJ, Schmiemann V, Kiel S, Böcking A, Kappes R, Gabbert HE, Sarbia M (2004) Aberrant methylation of the adenomatous polyposis coli promoter 1A in bronchial aspirates from patients with suspected lung cancer. Int J Cancer 110:751–755

Li W, Deng J, Jiang P, Tang J (2010) Association of 5′-CpG island hypermethylation of the FHIT gene with lung cancer in southern-central Chinese population. Cancer Biol Ther 10:997–1000

Nakata S, Sugio K, Uramoto H, Oyama T, Hanagiri T, Morita M, Yasumoto K (2006) The methylation status and protein expression of CDH1, p16(INK4A), and fragile histidine triad in nonsmall cell lung carcinoma: epigenetic silencing, clinical features, and prognostic significance. Cancer 106:2190–2199

Tomizawa Y, Iijima H, Nomoto T, Iwasaki Y, Otani Y, Tsuchiya S, Saito R, Dobashi K, Nakajima T, Mori M (2004) Clinicopathological significance of aberrant methylation of RARbeta2 at 3p24, RASSF1A at 3p21.3, and FHIT at 3p14.2 in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 46:305–312

Wistuba II, Gazdar AF, Minna JD (2001) Molecular genetics of small cell lung carcinoma. Sem Oncol 28:3–13

Ekim M, Caner V, Büyükpinarbaşili N, Tepeli E, Elmas L, Bagci G (2011) Determination of O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase promoter methylation in non-small cell lung cancer. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 15:357–360

Lai JC, Cheng YW, Goan YG, Chang JT, Wu TC, Chen CY, Lee H (2008) Promoter methylation of O(6)-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase in lung cancer is regulated by p53. DNA Repair (Amst) 7:1352–1363