Abstract

Background

Complete resection is the only definitive treatment available for gastric cancer. Factors associated with positive margins and their survival effects have been the subject of many studies, but the appropriate management for these patients is still debated. The objective of this review is to examine positive margins after gastric cancer resections by exploring predictive factors, impact on survival, and optimal strategies for re-resection.

Methods

A systematic electronic literature search was conducted using Medline and EMBASE from January 1, 1998, to December 31, 2009. Studies on gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma that either investigated the predictors for positive margin or employed multivariate methods to analyze the survival effects of positive margins were selected.

Results

Twenty-two studies incorporating 19355 patients were included in this review. Positive margins were associated with larger tumor size, deeper wall penetration, more extensive gastric involvement, greater nodal involvement, higher stage, diffuse histology, higher Borrmann type, lymphatic vessel involvement, and total gastrectomy. Patient survival was independently associated with margin status, and this survival effect was more prominent in early cancers in most studies that performed subgroup analyses.

Conclusions

The probability of acquiring positive margins is highly dependent on the biology and the extent of the tumor. There is a significant negative effect on survival, which is more prominent in cancers at early stages, making re-resection or a second operation important. Patients with more advanced disease can be offered more extensive surgery to remove disease, but this should be balanced against the risks of more extensive resections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the criteria of the International Union against Cancer (UICC)/American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) system, curative (R0) resection is defined as the en-bloc resection of the primary cancer completed without any residual microscopic or macroscopic disease. If any microscopic disease is detected at the surgical margin, the surgery should be recognized as an R1 resection, and macroscopic residual tumor after surgery changes the status to R2 [1]. Quality gastric cancer surgery, defined as R0 resection with a lymphadenectomy that includes a minimum assessment of 16 or more lymph nodes, should be the surgeon’s goal in the elective setting [2, 3]. Due to the submucosal spread of gastric cancer, a grossly normal resection margin is often insufficient to ensure pathological clearance; consequently, resection of 6 cm of grossly normal adjacent tissue has been recommended when technically feasible [4]. The prevalence of positive margins in resected gastric cancer patients shows wide variability, from 0.8 to 20.0% in reported series [5], and its detrimental survival effect has been demonstrated in many studies [2, 3, 6–17]. However, the independent effect of positive margins on long-term survival may be confounded by coexistent advanced disease, reflected in the extent of nodal involvement, depth of invasion, and histologic subtype. In addition, the criteria for re-resection in patients with positive margins after curative-intent gastrectomy have not been defined. Therefore, the goal of the present study was to systematically review the literature relevant to the surgical margin status, in order to: (1) identify the predictive factors for positive margins, (2) assess the effects of positive margins on survival, and (3) identify the selection criteria for re-resection of patients with positive margins.

Methods

Data sources

An electronic literature search was conducted in Medline and EMBASE from January 1, 1998, to December 31, 2009, according to the search algorithm presented in the Appendix of Supplementary material. Search terms included: exp Stomach Cancer/ or [((gastric or stomach) adj1 cancer$) or ((gastric or stomach) adj1 carcinoma) or ((gastric or stomach) adj1 adenocarcinoma) or ((gastric or stomach) adj1 neoplasm$).mp.] and [((negative or resection) adj2 margin$).mp. or exp frozen section/ or exp GASTRECTOMY/ or ((gastric or stomach) adj2 resect$).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name] or [omentectom$.mp. or multivisceral resection$.mp.] and [clinical trial/ or controlled clinical trial/ or exp comparative study/ or meta analysis/ or multicenter study/ or exp practice guideline/ or randomized controlled trial/] not [Case Report/ or review]. A separate search of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (1998–2009) was performed using the search term “gastric cancer”. The literature search was limited to English-language and primary reports. No attempt was made to locate unpublished material.

Study selection and review process

To be eligible, studies had to meet all the following criteria: (1) include patients with gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma, (2) investigate predictors for positive margins, or employ multivariate analysis methods to analyze the effects of positive margin on survival, and (3) be published in English in a peer-reviewed journal. Studies were excluded according to the following criteria: (1) reviews, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, abstracts, editorials or letters, case reports, and guidelines, or (2) studies involving <30 patients. If multiple studies were published from the same set of patients, the most inclusive one was utilized. All electronic search titles, selected abstracts, and full-text articles were independently reviewed by a minimum of two reviewers (NC, RC, LH, and HR). Reference lists from review papers and relevant articles were also examined for additional studies that met our inclusion criteria. Disagreements on study inclusion/exclusion were resolved with a consensus meeting of the reviewers.

Data extraction

A systematic approach to data extraction was used to produce a descriptive summary of participants, interventions, and study findings (Table 1). The first reviewer (HR) independently extracted the data and a second reviewer (RC) checked the data extraction. No attempt was made to contact authors for additional information.

Results

Studies

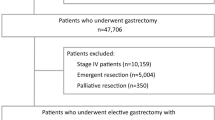

A total of 3608 potentially relevant abstracts were identified for preliminary review from the electronic and manual searches; 136 articles were reviewed, and 22 were selected for data abstraction (Fig. 1). Seven studies [2, 5, 7, 14, 18–20] investigated both predictive factors and survival effects of positive margins. Another 15 studies evaluated the relationship of survival and positive margins [3, 6, 8–13, 15–17, 21–24]. In total, these studies included 19355 patients, with an R0 resection rate ranging from 27 to 91.5%, reflecting both the heterogeneity in patient inclusion criteria, and the indications for surgery (Table 1).

Associations of tumor-related factors with positive resection margin

The extracted data comparing clinical and pathological variables between positive and negative margin resections are summarized in Tables 2 and 3. Margin status was the independent variable with which other variables were compared. Gender and age were not associated with margin status in the studies that reported these data [2, 5, 19, 20]. Gastric cancer was more common in males in all studies, and most patients were in their sixth and seventh decades of life.

Many factors related to tumor biology and stage were found to be associated with a positive margin. Tumor location was demonstrated to differ between positive- and negative-margin groups. The studies by Kim et al. [2], Cho et al. [19], Sun et al. [5], Wang et al. [20], and Cascinu et al. [18] concluded that total gastric involvement was significantly more common in patients with positive margins compared to those with negative margins (Table 2). On both univariate and multivariate analyses, resections with a positive margin were associated with larger tumor size in the two studies that reported this variable [5, 20] (Tables 2, 3).

T3 and T4 tumors were significantly more common in the positive-margin group [2, 5, 7, 19, 20] (Table 2), and higher T stage was independently associated with a positive margin on multivariate analysis in the studies by Cho et al. [19], Sun et al. [5], Wang et al. [20], and Morgagni et al. [14] (Table 3). In all studies that evaluated nodal spread in univariate analysis, higher N status was significantly more common in the positive-margin group [2, 5, 7, 14, 19, 20] (Table 2). On multivariate analyses, higher N stage was reported as an independent risk factor for a positive margin in the studies by Sun et al. [5] and Wang et al. [20] only. Although all studies employed the UICC/AJCC TNM system, the versions used were different. The fourth edition [25], used by Kim et al. [2] and Chan et al. [7], did not include the N3 subgroup, and node staging was based upon the distance from the edge of the primary tumor. In the fifth edition [1], pN staging was based on the number of involved nodes, and pN3 was introduced as more than 15 metastatic lymph nodes. In the 5th and 6th editions, T4N+ and N3 tumors were classified as stage IV [1, 26]. Therefore, surgery for stage IV disease may have been considered curative using some versions of the UICC/AJCC system.

There were other tumor-related variables associated with margin status. Lymphatic vessel invasion was only evaluated in the study by Sun et al., where positive-margin tumors were associated with invasion of lymphatic vessels [5] (Table 2). Lauren’s classification was reported in three studies [2, 5, 14], which observed an association between positive margins and a diffuse histology. Morgagni et al. further found that this association was independently statistically significant [14] (Table 3). Supporting this, Sun et al. [5] and Kim et al. [2] found that patients with a negative margin more often had an intestinal subtype gastric cancer (Table 2). Poorly differentiated tumors were associated with a positive margin in the studies by Cho et al. [19], Sun et al. [5], Wang et al. [20], and Cascinu et al. [18]. In the same studies, a negative margin resection was more commonly seen in the group with well-differentiated tumors (Table 2). Only three studies examined tumors by Borrmann type [5, 14, 19], and Borrmann type IV tumors were significantly associated with positive postoperative margins in all three studies (Table 2).

Survival factors

Resection-line tumor infiltration was strongly associated with survival. On univariate analysis, a positive resection margin was a negative prognostic factor in 17 studies [2, 5, 7–11, 13–16, 18–20, 22–24] (Table 4). In only one study—which explored the effects of distal positive margin in esophageal and esophagogastric junction (EGJ) cancers, with a high percentage of advanced-stage cancers—was margin status not a survival factor [21]. Four studies did not report the results of a univariate analysis, but showed that a positive margin was a significant predictor of survival on adjusted analysis [3, 6, 12, 17]. A positive margin was associated with poor prognosis as an independent factor by multivariate analysis in 14 studies [2, 3, 6–17]. However, in 3 studies [22–24] the survival effect of a positive margin status lost its prognostic effect after adjustments for other confounding factors of aggressive biology (Table 4).

The survival effects of positive margins were not universal. The studies that performed subgroup analysis to explore these effects in different T, N, and AJCC stage groups [2, 5, 14, 18–20] showed that margin status was a significant independent survival factor mostly in early-stage disease (Table 5). T stage appears to modify the degree to which a positive margin is associated with survival [5, 14]. Sun et al. demonstrated that positive margins were a negative predictive factor in patients with T1 and T2, but not in those with T3 and T4 tumors [5] (Table 5), whereas Morgagni et al. reported that a positive margin was a survival factor in patients with T2 and T3, but not in those with T1 and T4 tumors. In the study by Morgagni et al., all early gastric cancer patients with positive margins presented only lateral infiltrated margins at the suture site. Therefore, they suggested that poor blood supply at the resection margin may prevent cancer growth, justifying the good survival rates for T1 patients with positive margins [14].

Comparing the groups without nodal infiltration with those in whom nodes were involved, multivariate analysis by Cho et al. [19] and Cascinu et al. [18] showed that a positive margin was an independent negative prognostic factor only in patients with no nodal involvement (Table 5). However, other studies indicated that a positive margin was a negative prognostic factor even in node-positive patients [2, 5, 14]. The analysis by Kim et al. showed that positive margins remained an independent survival factor in patients with 5 or fewer positive lymph nodes [2]. Likewise, in the study by Sun et al., margin involvement was a negative prognostic factor in patients grouped as N0 and N1 according to the UICC/AJCC 6th edition [5]. However, Morgagni’s group was able to show that a positive margin retained an unfavourable survival effect even in the N2 group, by UICC/AJCC 5th edition staging criteria [14].

In addition to T and N staging, Sun et al. [5] performed a subgroup analysis based on overall tumor stage, concluding that a positive margin had no independent survival effect in advanced stage (III and IV) tumors (Table 5). Contrary to that, Wang et al. [20] reported that margin was a survival factor irrespective of stage, and Morgagni et al. [14] showed that positive margins affected survival in stage III patients.

It seems reasonable to perform re-resection only in the groups in which margin status shows survival implications. In practical terms, this was demonstrated in only one study of re-excision for a positive margin. Kim et al. [2] demonstrated that re-excision based on frozen section results had a positive survival benefit only in those patients with ≤5 positive nodes, the same subgroup in which positive margins were associated with survival on adjusted analysis. Although not explicitly examined, suggestions for management of positive margins were made by other included studies. Sun et al. recommended that frozen sections should be performed to avoid a positive margin in T1 patients, due to a high incidence of locoregional recurrence (40%) and the significantly worse prognosis. They also suggested that patients with N0–1, T1–2, stage I–II disease and positive margins would benefit from re-resection, as the prognosis for these patients was found to be significantly worse, and the incidence of recurrence was high [5]. Wang et al. [20] recommended the use of intraoperative frozen sections to determine the extent of the resection margin. Cascinu et al. [18] proposed reoperation for positive-margin and N0-stage disease, and close follow up for patients with positive lymph nodes, without the need for a more aggressive surgical approach.

Discussion

The negative effects of positive margins on patient survival and the predisposing factors for residual cancer have been the subjects of many studies [2, 3, 5–24, 27–31]. Yet the management of positive margins is a dilemma, considering the risks of a second operation or a more extensive primary resection. In this review, residual tumor at the resection margin was evaluated from two different perspectives: the predisposing factors for a positive margin resection, and the effects of a positive margin on survival. In addition, this review aimed to explore the subgroups in which a patient with a positive margin should be offered a more extensive primary resection if detected intraoperatively, or a re-operation if the positive margin is determined on final pathology assessment.

The studies included in this review were heterogeneous in their inclusion criteria and surgical techniques (Table 1). R2 resections were included in some, and the R0 resection rate varied considerably among studies. In series that excluded R2 resections, R0 rates ranged from 78.1 to 98.2% [2, 7, 13, 15, 18, 20, 21], perhaps due to differences in patient factors, tumor characteristics, surgical techniques, or surgeon expertise. For instance, Cho et al. [19] attributed their low rate of positive microscopic margins (98.2% R0 rate) to the expertise of surgeons, preoperative endoscopic assessment, and routine frozen section examinations.

Tumor characteristics were found to be an important predisposing factor for positive resection margins. Positive margins were associated with more aggressive tumor biology: larger tumor size, deeper wall penetration (T stage), more extensive gastric involvement, greater number of nodes involved, advanced stage, diffuse histology type, higher Borrmann type, and lymphatic vessel involvement. Total gastrectomy was also associated with positive margins, which is likely a surrogate for more extensive disease. These aggressive tumor characteristics allow the identification of patients at risk for positive margins, and thus identify a subset of patients in whom greater gross margins or intraoperative frozen assessment of margin status is warranted.

Margin status is an important consideration in patients’ survival, but loses prognostic significance in patients with advanced disease in most studies. The reason for this loss of independent association with survival is likely the more dominant negative survival effect of advanced stage compared to margin status. Patients with advanced cancers are more likely to die of carcinomatosis or disseminated disease than anastomotic recurrence [5].

However, there are some inconsistencies in these survival findings (Table 5). First, unlike the majority of the studies where positive margins negatively affected survival only in early stages, Wang et al. found that positive margins were a marker for significantly decreased survival irrespective of tumor stage. Thus, these authors recommend re-operation even for patients who are node-positive and margin-positive [20]. Second, the subgroups in which positive margins have independent prognostic significance are not consistent among different studies, including N2, T3, and stage III cancers in one study [14]. The reason might be the number of patients, different operative technique, patient selection, or study design. Despite these inconsistencies, it seems that margin status is associated with survival mainly in patients with lower N and T stage. Similarly, the prognostic importance of lymph node involvement has been examined in series of multivisceral resections for gastric cancer [32–35], with most finding no survival benefit for extended resections in patients with extensive lymph node involvement. However, in a few patients with advanced nodal disease, long-term survival was achieved (11% 5-year overall survival) [36].

An important caveat in the interpretation of survival data is the extent of lymphadenectomy and the issue of stage migration, as raised by Sano et al. [37]. They reason that unless at least a D2 dissection is performed and N stage is accurately assessed, the survival effects of positive margins in N+ patients cannot be accurately compared to those in N0 patients. Furthermore, in studies which compared survival in N0 stage with that in all N+ cases, such as the studies of Cho et al. [19] and Cascinu et al. [18], it was found that although margin status may have a significant effect on survival in the subgroup with limited nodal involvement, this effect could be masked by the poor survival of those with more extensive nodal disease.

The results of this review can be employed to predict the probability of positive margins, by a careful preoperative assessment of the features which are independently associated with positive margins (Table 3). While the pathological T-stage is unknown at the time of the operation, preoperative predictors such as tumor size, differentiation, and endoscopic ultrasound results should influence the grossly negative margin that surgeons aim to achieve. Additionally, intraoperative frozen sections should be considered to avoid positive margins. The accuracy of frozen sections is reported to be 97.8% [38]. A positive margin may be dealt with more easily at the time of the initial operation, as opposed to making a decision regarding repeat laparotomy for further resection. Although patients with earlier stage cancers are less likely to have a positive margin, the survival impact in early-stage patients is worse. Therefore, the policy of frozen sections for all patients, as advocated by Wang et al. [20], is a reasonable approach.

Recommendations regarding the management of positive margins vary. Some authors believe that patients with positive margins should only be watched closely [27], while others recommend re-resection for all patients, irrespective of their stage [20]. If a positive margin is found, the surgeon must balance the risks of further resection against the benefit of an R0 resection. The additional resection necessary to achieve negative margins ranges from a simple resection of additional gastric tissue, to additional resection of the esophagus, to a pancreaticoduodenectomy. Unfortunately, achieving a negative margin by extending the resection might not improve survival in all patients. Therefore, it would be most reasonable to offer re-resection or an extended resection only to those patients in whom margin status is independently associated with improved survival.

The majority of the studies reviewed [2, 5, 18, 19] support the idea that lymph node status is the most important predictor of whether a patient will benefit from resection to negative margins. Given the retrospective nature of the data, along with confounding indications for performing extended resections, such as patient comorbidities, and patient and physician bias, it is difficult to create strict criteria for re-resection or extended resection. However, re-resection or extended resection appears to have the most obvious survival benefit in N0, N1, and earlier T-stage patients.

Only 2 of the papers reviewed reported the utility of adding neoadjuvant chemotherapy to surgery [9, 13], but they did not discuss whether this could decrease positive margin rates. There is no evidence that downstaging, utilizing preoperative chemotherapy or chemoradiation, reduces the incidence of positive margins, or improves survival. Kim et al. [2] have shown that postoperative radiation and chemotherapy are not effective in improving the survival of patients with positive margins. However, in patients in whom positive margins are an obvious concern on preoperative investigations, the involvement of a multidisciplinary team is of utmost importance [39].

The major limitation of the present review is the heterogeneity of the included studies in terms of their data collection, inclusion criteria, variables, and staging systems. Additionally, study designs were mostly retrospective single-institution series. The addition of neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiation may be an important consideration for patients with advanced disease, but could not be addressed in this review. Given the inconsistencies of the relationship between stage and survival benefits, future prospective studies are needed to definitively answer the question of which patients will benefit from re-excision.

In conclusion, this review demonstrates that a complex interaction of tumor biology, cancer stage, and surgical technique affects the probability of positive surgical margins and patient survival. Among biologic determinants, T stage, N stage, tumor size, and histology are independent predictive factors of positive margins and can be evaluated preoperatively, to anticipate confronting a positive margin. Intraoperative frozen sections should be performed to decrease the occurrence of postoperative detection of positive margins in patients undergoing curative gastrectomy. The effect of margin status on survival seems to be most prominent for patients with earlier stage disease (N0–1 and T1–2), and these patients are the best candidates for re-resection, or a second operation. Patients with more advanced disease can be offered more extensive surgery to remove disease, but this should be balanced against the risks of more extensive resections.

References

Fleming ID, Cooper JS, Henson DE, Hutter RVP, Kennedy BJ. AJCC cancer staging manual. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1997.

Kim SH, Karpeh MS, Klimstra DS, Leung D, Brennan MF. Effect of microscopic resection line disease on gastric cancer survival. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3(1):24–33.

Siewert JR, Bottcher K, Stein HJ, Roder JD. Relevant prognostic factors in gastric cancer: ten-year results of the German Gastric Cancer Study. Ann Surg. 1998;228(4):449–61.

Bozzetti F, Bonfanti G, Bufalino R, Menotti V, Persano S, Andreola S. Adequacy of margins of resection in gastrectomy for cancer. Ann Surg. 1982;196(6):685–90.

Sun Z, Li DM, Wang ZN, Huang BJ, Xu Y, Li K. Prognostic significance of microscopic positive margins for gastric cancer patients with potentially curative resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(11):3028–37.

An JY, Kang TH, Choi MG, Noh JH, Sohn TS, Kim S. Borrmann type IV: an independent prognostic factor for survival in gastric cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12(8):1364–9.

Chan WH, Wong WK, Khin LW, Chan HS, Soo KC. Significance of a positive oesophageal margin in stomach cancer. Aust N Z J Surg. 2000;70(10):700–3.

Dicken BJ, Saunders LD, Jhangri GS, de Gara C, Cass C, Andrews S. Gastric cancer: establishing predictors of biologic behavior with use of population-based data. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11(6):629–35.

Johansson J, Djerf P, Oberg S, Zilling T, von Holstein CS, Johnsson F. Two different surgical approaches in the treatment of adenocarcinoma at the gastroesophageal junction. World J Surg. 2008;32(6):1013–20.

Kim JH, Jang YJ, Park SS, Park SH, Kim SJ, Mok YJ. Surgical outcomes and prognostic factors for T4 gastric cancers. Asian J Surg. 2009;32(4):198–204.

Kycler W, Teresiak M, Łoziński C. Prognostic factors for patients with gastric cancer after surgical resection. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2006;11(5):235–46.

Lello E, Furnes B, Edna TH. Short and long-term survival from gastric cancer. A population-based study from a county hospital during 25 years. Acta Oncol. 2007;46(3):308–15.

Mariette C, Castel B, Balon JM, Van Seuningen I, Triboulet JP. Extent of oesophageal resection for adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2003;29(7):588–93.

Morgagni P, Garcea D, Marrelli D, De Manzoni G, Natalini G, Kurihara H. Resection line involvement after gastric cancer surgery: clinical outcome in nonsurgically retreated patients. World J Surg. 2008;32(12):2661–7.

Nazli O, Derici H, Tansug T, Yaman I, Bozdag AD, Isguder AS. Survival analysis after surgical treatment of gastric cancer: review of 121 cases. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54(74):625–9.

Samson PS, Escovidal LA, Yrastorza SG, Veneracion RG, Nerves MY. Re-study of gastric cancer: analysis of outcome. World J Surg. 2002;26(4):428–33.

Takahashi I, Matsusaka T, Onohara T, Nishizaki T, Ishikawa T, Tashiro H. Clinicopathological features of long-term survivors of scirrhous gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47(35):1485–8.

Cascinu S, Giordani P, Catalano V, Agostinelli R, Catalano G. Resection-line involvement in gastric cancer patients undergoing curative resections: implications for clinical management. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1999;29(6):291–3.

Cho BC, Jeung HC, Choi HJ, Rha SY, Hyung WJ, Cheong JH. Prognostic impact of resection margin involvement after extended (D2/D3) gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: a 15-year experience at a single institute. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95(6):461–8.

Wang SY, Yeh CN, Lee HL, Liu YY, Chao TC, Hwang TL. Clinical impact of positive surgical margin status on gastric cancer patients undergoing gastrectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(10):2738–43.

Casson AG, Darnton SJ, Subramanian S, Hiller L. What is the optimal distal resection margin for esophageal carcinoma? Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69(1):205–9.

Kodera Y, Yamamura Y, Ito S, Kanemitsu Y, Shimizu Y, Hirai T. Is Borrmann type IV gastric carcinoma a surgical disease? An old problem revisited with reference to the result of peritoneal washing cytology. J Surg Oncol. 2001;78(3):175–81 (discussion 81–2).

Piessen G, Messager M, Leteurtre E, Jean-Pierre T, Mariette C. Signet ring cell histology is an independent predictor of poor prognosis in gastric adenocarcinoma regardless of tumoral clinical presentation. Ann Surg. 2009;250(6):878–87.

Shiraishi N, Adachi Y, Kitano S, Bandoh T, Inomata M, Yasuda K. Gastric cancer with extragastric lymph node metastasis: multivariate prognostic study. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3(4):211–8.

Beahrs OH, Henson DE, Hutter RVP, Kennedy BJ. AJCC cancer staging manual. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1992.

Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, Fritz AG, Balch CM, Haller DG. AJCC cancer staging manual. 6th ed. New York: Springer; 2002.

Papachristou DN, Agnanti N, D’Agostino H, Fortner JG. Histologically positive esophageal margin in the surgical treatment of gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 1980;139(5):711–3.

Hockey MS, Fielding JWL, Kelly KA. Resection line disease in stomach cancer. Br Med J. 1984;289(6445):601–3.

Shiu MH, Moore E, Sanders M, Huvos A, Freedman B, Goodbold J. Influence of the extent of resection on survival after curative treatment of gastric carcinoma. A retrospective multivariate analysis. Arch Surg. 1987;122(11):1347–51.

Gall CA, Rieger NA, Wattchow DA. Positive proximal resection margins after resection for carcinoma of the oesophagus and stomach: effect on survival and symptom recurrence. Aust N Z J Surg. 1996;66(11):734–7.

Songun I, Bonenkamp JJ, Hermans J, van Krieken JH, van de Velde CJ. Prognostic value of resection-line involvement in patients undergoing curative resections for gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A(3):433–7.

Jeong O, Choi WY, Park YK. Appropriate selection of patients for combined organ resection in cases of gastric carcinoma invading adjacent organs. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100(2):115–20.

Zhang M, Zhang H, Ma Y, Zhu G, Xue Y. Prognosis and surgical treatment of gastric cancer invading adjacent organs. ANZ J Surg. 2010;80(7–8):510–4.

Kitamura K, Tani N, Koike H, Nishida S, Ichikawa D, Taniguchi H, et al. Combined resection of the involved organs in T4 gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47(36):1769–72.

Ozer I, Bostanci E, Orug T, Ozogul Y, Ulas M, Ercan M, et al. Surgical outcomes and survival after multiorgan resection for locally advanced gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 2009;198(1):25–30.

Saito H, Tsujitani S, Maeda Y, Fukuda K, Yamaguchi K, Ikeguchi M, et al. Combined resection of invaded organs in patients with T4 gastric carcinoma. Gastric Cancer. 2001;4(4):206–11.

Sano T, Mudan SS. No advantage of reoperation for positive resection margins in node positive gastric cancer patients? Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1999;29(6):283–4.

Ferriero JA, Myers JL, Bostwick DG. Accuracy of frozen-section diagnosis in surgical pathology—review of a 1-year experience with 24,880 cases at Mayo-Clinic Rochester. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70(12):1137–41.

Mcdonald JS. Gastric cancer—new therapeutic options. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(1):76–7.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Canadian Cancer Society (Grant #019325). Dr. Coburn is supported by a Ministry of Health and Long Term Care Career Scientist Award. Dr. Law is supported by the Hanna Family Chair in Surgical Oncology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Raziee, H.R., Cardoso, R., Seevaratnam, R. et al. Systematic review of the predictors of positive margins in gastric cancer surgery and the effect on survival. Gastric Cancer 15 (Suppl 1), 116–124 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-011-0112-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-011-0112-7